MC history students of today discover that the Monmouth College of 100 years ago was a vibrant and turbulent place

| |

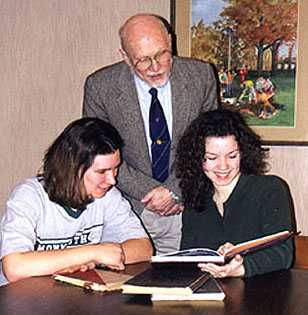

| Julia Ross (left) and Jennifer Rund, under the supervision of Professor William Urban (standing), peruse vintage Monmouth College annuals to develop insight into campus life a century ago. they were among four of Urban's students who last fall delved into the college's past and turned up some surprising stories. | |

April 27, 1999 Web posted at: 10 a.m. CDST

Marking the passage of time in 100-year blocks is a characteristic of modern civilization that provides us an opportunity to look back, to see what has changed and what has not. we desire to see progress and continuity alike, to know that we have neither wasted our years nor broken completely with what was good.Monmouth College's alumni, faculty and staff, and friends may find a look at our alma mater a century ago both reassuring and disquieting. In those days there was rapid change in educational methods, cutthroat competition for students, social unrest, financial crisis, and war. It was a moment when the survival of the college was far from assured, but it was also a time when its friends were passionate in their loyalty and support.

The students in the fall 1998 historiography class investigated four aspects of Monmouth College in 1898-1901: Ross wrote about President Samuel Lyons and his academic reforms; Rund wrote about social life on campus; Johnson wrote about the college's finances; and Hoffman wrote about the Spanish-American War on campus and in the community. They presented their findings in early April at a Phi Alpha Theta history honorary society conference at Bradley University in Peoria.

The community was brought together by the excitement--the whistles and bells announcing every American victory brought students and townsfolk out into the streets to cheer.

| |

| The Rev. S.R. Lyons, himself a graduate of Monmouth College, was at first hailed as a populist president who would be a friend and inspiration to students and faculty alike. Financial crises and political intrigue, however, would soon immerse him in controversy and send him packing.. | |

Lyons' Reforms

President Samuel Ross Lyons came to office in June 1898 better prepared for his job than either of his predecessors, David Wallace or Jackson B. McMichael. He was a veteran of the Civil War, an 1877 MC graduate, a successful pastor in Bloomington, Indiana, an active participant in the Synods of the Presbyterian Church (including some held on the Monmouth campus), and had been a member of the governing boards of Monmouth College and Indiana State University. His first wife, Elizabeth Irwin (also an 1877 Monmouth College graduate) had died nine years before, leaving him with two daughters now of college age, and his second wife, Althea Cooper, had given birth to three children in six years. Lyons saw that the academy was in its last days, outmoded by the public high school; hence, it could not alone continue to feed students into the college in sufficient numbers to prevent Monmouth College from joining the ranks of local colleges that were going under--Lombard, Vashti, and Hedding.

His first task was to update the curriculum. By introducing the Group Plan he established departments and courses of study that everyone would recognize today. Through this secularization of studies Lyons hoped to attract more students than the older emphasis on training ministers and missionaries had done. In 1900, the Ravelings could proclaim, "The future is full of promise. The number of students is increasing every year. The endowment will be doubled before commencement. That means more departments and better work. It means the inception of the Greater Monmouth College."

|

The jubilation was premature. The increase in enrollment in 1898 was small (from 235 to 277), and the next year it was back to 239; the tuition was deliberately low in any case (providing $3700 in 1898-99, but only $2300 the next year). It was the president's task to recruit students, hire new faculty, and raise money. Because this necessitated his traveling far and wide, Lyons left the management of the college business in the capable hands of Professor John Wilson and the demanding campus social life to his overworked wife. His travels must have interfered, too, with his effort to contribute to instruction (in those days, when everyone did a bit of everything, one was either liberally educated or unemployable).

Social Life at MC Because the total enrollment of the college was small, social life had to involve everyone, and since the students lived with families all across town, it could not be spontaneous. Planning and preparation were necessary for every activity, and this was a very formal era. Only picnics could be completely informal--and even then, carriages and a site had to be provided. Stiff clothing, rigid manners, and an emphasis on propriety were essential to making ladies and gentlemen out of the high-spirited lads and lasses of the Gay Nineties.

The four literary societies were the heart of social and out-of-class intellectual life. There were two societies for men, two for women, to which the YMCA/YWCA, the Christian Union and the Second Presbyterian Church (now Faith Presbyterian) had to be added. Sororities and fraternities were banned because of their insistence on secrecy--and a progressive institution like Monmouth College, where every progressive idea flourished (Lyons' brother had given the commencement address a few years before and had favorably discussed the topic of socialism; Darwin was taught without reservation, and was even invoked by Lyons as a principle in the struggle of individual colleges to survive) would not risk anything like the KKK or the Knights of the Golden Circle becoming active on campus. Boarding clubs like "Lucky 13,"' the Boynton Club, and the Casino Club were popular, as were the mandolin club, the glee club and other musical organizations.

Sports were important. The college's new athletic facilities out on East Broadway were adequate for men's outdoor sports and a new instructor was hired to direct the women's physical training program. Indoor games were held in the downtown YMCA gym. But the big event of any year was the debate. In February 1899 a large party went to Des Moines for a full day of activities at Drake University. Pandemonium broke out among the Scots when the judges ruled Monmouth victorious.

Crisis and Tragedy

Lyons could not enjoy these triumphs fully because he was on the road continually. He was fortunate in finding a sympathetic ear in New York, Mr. James Law, who offered a veritable fortune, $50,000, if the president could raise a matching amount. Lyons came close enough to meeting the deadline that Law gave him an extension, during which Lyons found the needed donors. He appointed to the first Law chair in history to Florabel Patterson, whom he had sought out for the post, and he hired Luther Emerson Robinson, who was long considered the greatest teacher in the college history (Sam Thompson met "Robbie" during one holiday and immediately transferred to Monmouth College). Lyons began plans for a science building (ultimately J.B. McMichael Hall) and a library to join Old Main, the new Auditorium and the new gym (remembered by alums as the Little Theater), all of which he financed by selling lots to families wishing to build homes south of Broadway. Soon Monmouth College was no longer in the countryside, but well inside the city.

There was a momentary alarm that Western Illinois Teachers College would be established practically on the edge of campus, but the governor dismissed the board which had recommended a Monmouth site and named a new board which favored building the college in Macomb.

Lyons organized an investment program, in which Monmouth College paid annuities to investors. This meant that graduates and friends would have a retirement program better than could be provided by living off interest from the bank or from bonds; upon their death, the funds would revert to the college. This program--not unlike the present TIAA-CREF of today--would take time to work. Time was the one commodity Lyons did not have.

The crisis peaked in 1899 when the financial manager ran off with the ready cash. Faculty members had long suspected that something was wrong with the college books, and their concerns turned out to be worse than anyone had dreamed when they discovered $1,123 was missing. The fugitive was arrested and forgiven (in a truly Christian spirit typical of the college in that era) upon returning what was left of the money and promising restitution of the rest with six percent interest. But the episode demonstrated the need to reduce expenses.

Lyons planned to reduce the faculty and restructure it. By eliminating several senior faculty (some very senior, continuing to teach because there was no retirement plan and salaries had been too low to permit much savings), Lyons could cut the most expensive members of the staff, who were also the most opposed to his curricular reforms. This provoked a firestorm of protests which required many hours of meetings by the trustees of the college. In June 1900 the trustees ultimately rejected Lyons' demand to be given sole authority to hire and dismiss faculty, declaring that the charter reserved ultimate authority to the Senate and Trustees.

Much of this went unremarked by students and alums, who were only saddened by the retirement of some of the most beloved teachers from the academy and the college, among whom were Jenny Logue Campbell and "Johnny" Wilson. However, the discord bore hard on Mrs. Lyons, whose social contacts with the faculty were surely strained. On April 10, 1901, she went into the attic of the president's manor ("The Terrace," at the corner of Broadway and Ninth) and hanged herself. President Lyons shortly afterward resigned the presidency of Monmouth College.

The Spanish-American War

War had come and gone with such rapidity as to leave few traces in the college record. When the battleship Maine blew up on Feb. 16, 1898, war with Spain was practically inevitable. Excited by the yellow press and the genuinely oppressive conditions in Cuba, the young men went eagerly to the recruiting rallies and formed a college company of seventy-five men. But they were not needed. A well-trained local militia unit was mobilized by Col. George C. Rankin, but the War Department left them stranded in Springfield for a long time before finally sending them on a roundabout route to Puerto Rico. The only fatality was Lt. Lorenzo Cole, who had fallen with his horse in Springfield, then caught typhoid and finally pneumonia in Fort Wayne. He was an MC graduate and a physician.