by James L. De Young, PhD

Professor Emeritus of Communication and Theatre

History of Monmouth College Theatre

Little Theatre History - Dr. James De Young

Little Theatre History -Jeff Rankin

|

Monmouth

College Little Theatre History

by James L. De Young, PhD Professor Emeritus of Communication and Theatre

|

Although there were histrionic outlets in the debates and oratory taking place in the Monmouth College Literary Societies during the 19th century, the first record of legitimate dramatic activity was a series of scenes from Shakespeare apparently presented as a “Class Night Play” at the Pattee Opera House (in downtown Monmouth) as part of the 1894 Commencement.

Dramatic activity at Monmouth continued sporadically to the end of the century. It increased in frequency into the first quarter of the 20th century. Sustained play production by faculty and students increased with the hiring of Professor Ruth Williams in 1924. Miss Wiilliams was a speech teacher with a true love of drama and under her tutelage Crimson Masque, the college dramatic society, was founded in the fall of 1925. On the charter list of members was Dr. T.H. McMichael, president of the college and a current student, Jean Liedman. Miss. Liedman went on to get a PhD in Speech at the University of Wisconsin, returned to her alma mater to teach communications and head the Speech Department, and ultimately became the iconic Dean of Women (Dean Jean) whose name now graces Liedman Hall.

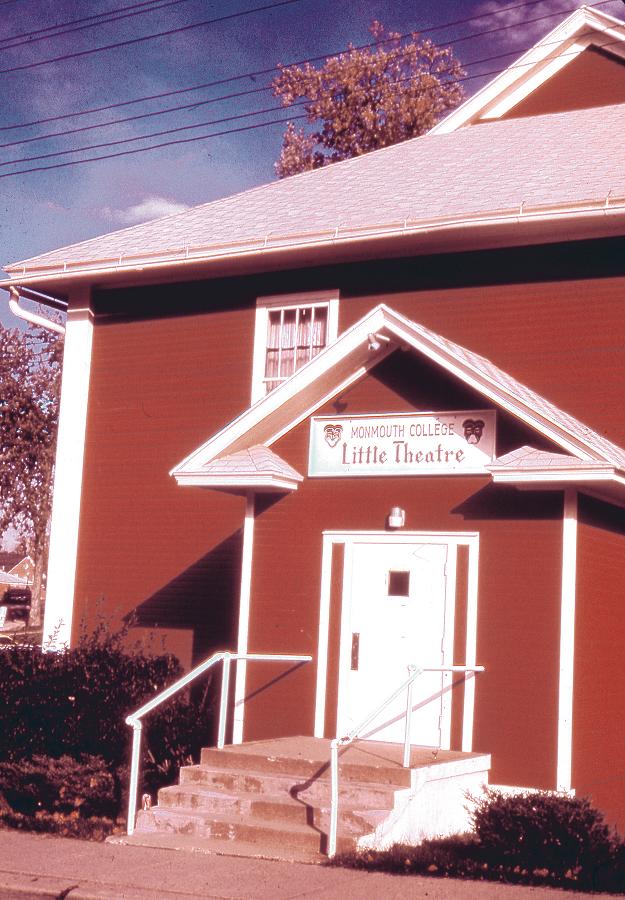

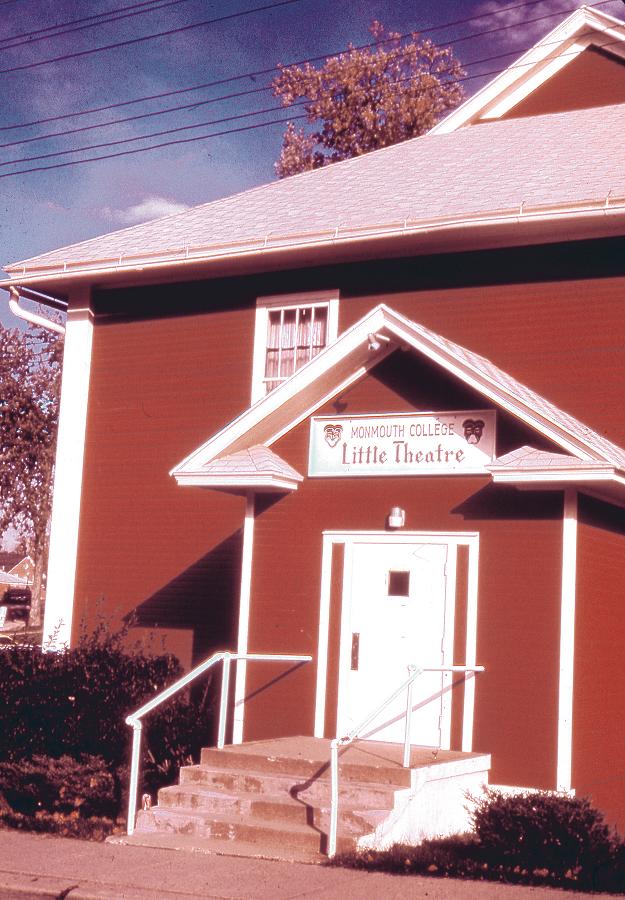

Drama acquired its first permanent home at Monmouth College in 1927 when Professor Ruth Williams and her students successfully petitioned the college trustees to turn over the old gymnasium (known as “Graham’s Cow Barn” or the “Old Crackerbox”) to Crimson Masque. The new Waid gymnasium had been completed in 1925 and the old gym, built in 1902, was standing empty waiting for demolition. Crimson Masque raised $350 to renovate it into a theatre and the first production was held there in October, 1927. Over the next sixty years it became known as “The Little Theatre” or “The Little Red Barn” or just “The Red Barn.” It went through scores of major and minor remodelings--even surviving a dangerous fire in 1934.

Ruth Williams remained the Director of Theatre at Monmouth College for twenty-three years until 1947. After her retirement a series of shorter termed faculty directors led the program.

Ralph Fulsom served from 1947-1950; Howard Gongwer from 1950-1956; Parker Zellers from 1956-1961; and Brooks McNamara from 1961-1963.

In the spring of 1963 Professor Liedman, then both head of the Speech Department and Dean of Women, hired James De Young to direct the theatre program. Dr. De Young held the Director of Theatre title for the next thirty-nine years-- with some breaks for a return to graduate school and to serve as the Faculty Director for ACM programs in London and Chicago. In his time at Monmouth Dr. De Young directed and/or supervised close to 150 productions. He also chaired the Communications and Theatre Department for a number of years.

Historically the key dramatic arts issue of the past forty-five years has been the growth of Theatre at Monmouth College from an extra-curricular option to an accredited academic program. Dr. De Young began his career as a one-person theatre program. He directed, designed, and supervised the building of all plays. By the time he retired in 2002, there were three fully qualified faculty members with professional degrees in Theatre. The Theatre curriculum had grown from a couple of courses as part of the Speech Department to a concentration within the Communication and Theatre Department. The culmination of this development occurred in 2007 when the college faculty approved a full-fledged major program for Theatre. For the first time in its history Monmouth College can offer majors in four important fine arts disciplines—Art, Music, Literature/Creative Writing, and Theatre.

The story of the Little Theatre has to end with a mention of its demise. Despite valiant efforts to create quality drama in the building, the 1902 converted gymnasium became an ever more constant trial for its occupants. Heating was inadequate, audience comforts minimal (you had to leave the building to go to the restroom), and backstage amenities were non-existent. For twenty-eight years the theatre staff dreamed and fought for a new purpose-built performance facility for Monmouth College. Finally in the spring of 1990, under the administration of President Bruce Haywood and supported by the financial generosity of many Crimson Masque alumni, the new Wells Theatre opened to the public. The old Little Theatre fell under the wrecking ball in the summer of 1990. Its former site is now occupied by a parking lot just to the west of Poling Hall and behind the Dahl Chapel.

Continuity provides significant strength in academic departments and the growth and success of the theatre program at Monmouth College in the last quarter century has been in large part due to the efforts and talents of Dr. Bill Wallace and Professor Doug Rankin, who joined the Department in 1979 and 1986 respectively. The Wells Theatre now offers a first class teaching and performance venue and with Professor Janeve West, a specialist in Acting and Directing, replacing Dr. De Young, the new major program in Theatre seems poised to create a bright new future for the Fine Arts at Monmouth College.

* Much of the early history of theatre at Monmouth College and the history of Crimson Masque in this summary depends on a student independent study done in 1978 by Dan Clay. (Doug Rankin will remember Dan Clay as he was in the cast of Equus with him.)

To my knowledge there has been no attempt to re-check Mr. Clay’s study or to formally update or chronicle the years since the study. It might be appropriate at this point to look for a student or a group of students who would be willing to undertake some new work in this area. Key to this would be that my memories and Doug’s and Dr. Wallace’s are still retrievable locally.

MONMOUTH, Ill. — Anyone who has only known Monmouth College’s exceptional physical plant during the past 25 years would find it hard to believe that for 90 years a crude wooden structure that cost $2,500 to build stood at the heart of campus. Not only did it stand, but it was heavily used throughout its lifetime and even survived a devastating fire.

Lovingly referred to as the “Old Crackerbox” or “Graham’s Cow Barn” (after the family that gave farmland to create the Monmouth College campus), the building began life as a gymnasium but for most of its existence served as headquarters for Monmouth’s progressive and respected drama program. Staging memorable productions that ranged from traditional Shakespeare to theater of the absurd, the college’s Crimson Masque organization made maximum use of the limited space through creative stagecraft and exceptional acting. Generations of alumni and local theatergoers fondly remember the old red barn as the Little Theatre.

Perhaps the reason the structure was so beloved is that it twice filled a vital need for students when finances were precarious for the fledgling college. The first instance was the demand for a gymnasium.

Although a Student Athletic Association was founded in 1877, it was not until 1894 that funds were raised to construct an athletic field for football, baseball and track. Still, students and alumni clamored for a gymnasium and, while the initial drawings for the Auditorium in 1894 included gym facilities, they were eventually removed for lack of funding.

College basketball gained popularity in 1897, when the YMCA bought the former Methodist Church in 1897 and installed a gymnasium, allowing Monmouth men to compete against area teams, but there was no college funding available for rental. The issue came to a head in 1900, when female students organized a basketball team but were not allowed to use the YMCA.

Early that year, after students formally petitioned President Lyons for a gym, the board agreed to match funds raised by students. In February, the trustees voted to sell 14 lots adjacent to the athletic park to help fund construction. On April 14, interim president J.H. McMillan turned the first shovelful of dirt on the project and work began on the foundation. The building was erected on the site of former tennis courts immediately behind the Auditorium, so that locker and bath facilities from that building could be shared.

It was reported that a large number of men had been employed to construct the gym, which would be completed in one month at a cost of $2,500. The 40 x 90-foot building would have a roof height of 20 feet, and because the basketball court ran wall-to-wall, a balcony-like running track encircling the building was erected 10 feet off the ground. It was also reported that the building would be veneered in brick when finances allowed. Perhaps predictably, that never happened.

By August, the gymnasium was finished but none of the apparatus had been purchased. It was not until September 1901 that equipment — in the form of bars, flying rings, punching bags and mats — would arrive. Still, by the end of 1900, the building had been equipped with two arc lights and provisions were being made for heating.

Because all Monmouth students were required to take physical education, the tiny building received constant use, but the congestion was relieved somewhat in 1914 when a gymnasium for women was erected on the third floor of the new McMichael Residence Hall. Finally, in 1925, a modern new college gymnasium replaced the aging structure, which was temporarily turned into a roller rink and social hall.

Enter Miss Ruth Williams, an energetic 26-year-old Northwestern University graduate, who was hired in 1923 to teach public speaking. An aficionado of theater, she was disappointed that Monmouth had no facilities for producing a play. Despite that, she organized the Crimson Masque thespian group and soon had 45 active members, along with 30 to 70 freshman apprentices. One-act plays were staged on the small stages of the four literary society rooms on the top floor of Wallace Hall. Each seated 105 people and contained a stage only three feet high. Full-length dramas required the use of the Auditorium stage, which couldn’t be easily reserved due to the required daily chapel service.

At the same time, a nationwide phenomenon known as the Little Theatre movement was gaining momentum. In 1927, theater writer Montrose Moses published an article in The North American Review explaining that the movement was the result of commercialization of the professional stage. “Accompanying this deterioration of the professional theatre is a rising interest in drama in all parts of the country,” he wrote. “A map of the United States drawn on the basis of much activity as I have suggested would show that professional theatre territory has shrunk nearly 50 per cent in the last quarter of a century, and that every state has its group of Little Theatres doing commendable producing and giving plays with the new philosophy of stagecraft…”

The Crimson Masque raised $350 and received permission to convert the old gym into a Little Theatre. Amenities were few, with no raked floor, limited lighting and seating consisting of bleachers in the rear and chairs in the front. The house sat 300 and admission was 25 cents. The Monmouth College Little Theatre opened Oct. 21, 1927, with three one-act plays, and over the next six decades would host nearly 200 increasingly sophisticated productions.

The aftermath of the

devastating 1934 fire.

The aftermath of the

devastating 1934 fire.Fire broke out early in the morning of June 5, 1934, following a dress rehearsal for senior play in the Auditorium. The cast had been using the Little Theater to dress and apply makeup, and the fire broke out in the men’s dressing room. Professor Richard Petrie, who was up late at his nearby residence grading exams, turned in the alarm just after 1 a.m. Most of the electrical equipment had been transferred to the auditorium for the class play and was saved.

A completely

renovated Little Theatre opened just months after the fire.

A completely

renovated Little Theatre opened just months after the fire.The contents of the building went up in flames but insurance money covered the loss and paid for the conversion into something more like a theater. The floor was slanted and the running track converted into balcony. A modern lighting system was installed, a scene dock built on the east end and cement steps replaced an old gangplank on the front.

Ruth Williams remained at the helm until after World War II. As male students went off to war, a town-and-gown group was formed so that townspeople could continue to supply male roles.

Howard Gongwer, who joined the theater faculty in 1950, began a modernization effort and spent one hot summer with a student rewiring the entire building so that the light control board could be moved from backstage to the rear of the theater. His successor, Parker Zellers, elevated the rear seats, constructed a vestibule and covered the radiators. His students installed a dimmer control and patch panel board, added a turntable, tape recorder and better speakers. He also installed a backstage sink and paint-mixing table. A tool cage was built and dressing rooms were improved with mirrors and lighting. An electric motor was installed to operate the curtain — its speed controlled by the gearshift from a 1928 Model A Ford.

“I shall never forget that old building,” Zellers recalled. “It was cold in the winter and stifling in the summer, but it was a sturdy old trouper. When a tornado knocked down some 50 trees on the campus, the old theatre remained unruffled and bone dry!”

Brooks McNamara, who became theater director in 1960, echoed Zellers’ complaint: “To my dying day I’ll never forget the experience of directing plays in the winter when cast, crew and director were forced to be bundled up in overcoats during much of the rehearsal period.”

Jim De Young, who began his Monmouth career as a one-person theater force in 1963, helped elevate theater at Monmouth from an extracurricular activity to an accredited academic program. Over the course of 39 years, he directed or supervised nearly 150 productions in the old red barn. When the former Carnegie Library was vacated in 1970, he saw the opportunity for a new theater venue on its second floor, which would include space for experimental theater, a costume shop and scenery/prop storage. More important, it could be used in the winter, in place of the always chilly Little Theatre. The new space was appropriately dubbed “Red Barn East.”

De Young’s handpicked successor, Doug Rankin, began acting in the original red barn while in high school. Now in charge of the modern Wells Theater, constructed in 1990, and the downtown experimental Fusion Theatre, created in 2014, he remembers the red barn with only a bit of nostalgia: “The fire escapes were made of wood, which kind of defeated the purpose. In the 1960s through early ’70s, there were about 10 lighting dimmers compared to more than 100 today. Of course, the only restroom was backstage so patrons had to go to the Auditorium.”

After serving as both a gymnasium and a theater for 90 years, the building known as “Graham’s Cow Barn” was finally razed in the summer of 1990, as the new Wells Theater was rising across campus. Pieces of the old structure were made into mementos for donors to the new facility.

Jeff Rankin is an editor and historian for Monmouth College. He has been researching, writing and speaking about western Illinois history for more than 35 years.