|

In This Issue:

Chicks

Dig It:

A Guy Reads A Bunch Of 'Chick-Lit'

By Alex Nall

Whenever someone asks me, “Hey, what did you read this summer?”

I become infuriated because my initial response is always “Not

enough!” That was the case this summer, yet again. I made a vow

to myself at the beginning of summer to read the classics:

Hemingway, Kerouac, maybe some Homer if I could squeeze it in.

This plan changed when a friend handed me a book and said, “Read

this. You’ll like it.” The name of the book was

The Girls’ Guide

To Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank. I looked at the book and

rolled my eyes, but not wanting to be rude, said I would “try it

out.”

The book’s protagonist is Jane, who throughout the seven stories

in the collection, ages in a non-linear model. At the beginning,

she’s fourteen observing her brother’s torrid relationship from

afar, then she is in her mid-twenties, dealing with the woes of

her own relationship issues, and in the last three stories she

moves in and out of a decaying relationship with an older man as

she ages.

On first look of the book’s synopsis I only had one phrase in my

head: Chick Lit. That fabled genre of pseudo-prose infused with

slop dialogue and ridiculous situations (Twilight fans can stop

reading now if they wish). At least that’s the impression I went

in with when starting out on this new literary adventure.

Surprisingly, I was enthralled by Jane’s commitment woes, her

scandalous and even saucy relationship with an older man, her

struggle with saying goodbye to her terminally-ill father and

the short terse sentences that spoke bluntly to her audience:

“That night, alone with all those empty beds, I couldn’t fall

asleep. I’d finished Gatsby and I looked out at the lagoon,

hoping to see a green light. But nobody’s dock was lit up. Only

one house had any lights on, and the light was just the blue of

a television set” (43). It was dialogue like this that spoke to

me as a person, rather than a male reader. I was able to

identify with the anxiety, confusion and bursts of joy in Jane’s

sporadic life. So I continued to read more “chick lit” and see

what else I could find.

I returned to a novella I had read in high school only because

it’s author, Steve Martin, was a really funny guy who was really

funny. The novella was Shopgirl and much like Bank’s story

collection, the prose was short, but formulated a deep sense of

awareness of the loneliness in all humans: “Weekends can be

dangerous for someone of Mirabelle’s fragility. One little

slipup in scheduling and she can end up staring at eighteen

hours of television” (23). The image of Mirabelle, waiting at

the counter at the glove department at Marcus Neiman’s, hoping

something will happen that will make her life start, stays

instilled in my head for its haunting universal outreach. I

wondered, after quickly revisiting Mirabelle and company, if the

male reader has completely misinterpreted the definition of

chick lit. Surely, all these books focused around contemporary

women’s lives couldn’t all be about the hardships of loneliness.

Once again, I found that this seemed to be the cause in Sylvia

Plath’s The Bell Jar, an autobiographical novel so emasculating

the reader is left haunted by Esther’s total lack of faith or

sanity in herself or the figurative “bell jar” world she is

trapped in: “I knew I should be grateful to Mrs. Guinea, only I

couldn’t feel a thing. If Mrs. Guiena had given me a ticket to

Europe, or a round the world cruise, it wouldn’t have made one

scrap or difference to me, because wherever I sat- on the deck

of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok- I would be

sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour

air” (175). Plath’s novel let me see into the challenges of

women suffering from depression, just as Martin’s Mirabelle and

Bank’s Jane allowed me to see the fixations and consciousness of

women in contemporary literature.

But none of these characters’ issues could amount to that of

Sethe in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which ended my summer reading

tour. The heartbreak and loneliness that Sethe suffers arises

from the ghosts of her daughter and slavery, which take hold of

her during the novel’s climax and almost squeeze every ounce of

life out of her. Morrison’s novel brought to bay my newfound

theory that the books I had been reading weren’t books about

depressed women, but were documents emphasizing the

psychological effects of different lifestyles, be it Jane’s

get-the-man now agenda, Mirabelle’s post-grad wandering,

Esther’s struggle to rise to literary fame, or Sethe’s

racially-scorned past.

After this experiment was over, I found myself revisiting some

works of feminine literature, finding things in them that I

hadn’t before. It occurred to me as I write this, that Jane

Austen satirized the “romance novels” so heavily adored by women

of her time in Northanger Abbey. If there is one thing I came

out learning from this experience, it’s this: books about women

aren’t novelized versions of Sex and The City episodes. Lovers

of literature—and male doubters, much like myself—should take

note that “chick lit” is thrown around too easily by the

seemingly “girly” subject matter and deceptive

misinterpretations. The puritan poet, Anne Bradstreet, said it

best: “For such despite they cast on female wits: If what I do

prove well, it won’t advance, They’ll say it’s stol’n, or else

it was by chance.” The alluring contrivance of “chick lit” is

that it isn’t about “chicks” at all, but is instead a unisex

form of literature that allows readers to look into the social,

historic and modern complications of the conflicts between

humans today.

Gendered Books: Why Girls Have Them and Guys Don't

By Leanna Waldron

While discussing books with a

few friends a couple of weeks ago, something one of them said struck

me.

“There’s no such thing as ‘guy books’.”

At first I was shocked by the sheer wrongness of

this statement. What about sci-fi, spy and adventure novels? What

about the ‘heroic quest’ and monsters and dragons? I insisted that

there were, indeed, ‘guy books'.

But that

got me thinking that I actually love those kinds of books. I mean,

give me dragons and epic battles over high school drama and romance

any day. I also know that many of my female friends feel the same

way. Yet if you ask most guys (and I’m definitely qualifying here by

saying “most”) if they’ve read Libba Bray’s Gemma Doyle trilogy or

Scott Westerfeld’s Uglies series, they would probably say no.

Both

of these series are in the fantasy or science-fiction genre and both

have a lot of action, conspiracy and adventure. So why are these

books labeled “girl books” and avoided by men while women are able

to read books like the Percy Jackson series without worrying about

the gender label being put on them?

I can’t help but wonder if it’s

the main characters that are really to blame, not the genre. It

seems to me that men don’t relate to strong female characters the

way that females can relate to strong characters of either gender.

If given a choice, I feel that most men would pick up

Eragon before

they picked up City of Bones.

Personally, almost all of my favorite

literary characters are male: Severus Snape of J.K. Rowling’s Harry

Potter series, Odd Thomas of Dean Koontz’s Odd Thomas series, Roland

Deschain of Stephen King’s Dark Tower series. To me, these

characters are characters first and men second. I relate to them

based on personality and not on what gender they are. So why does

it seem that men don’t feel the same way?

The gender question is

always a difficult one to answer, and I don’t think we’re going to

come to any clear conclusions anytime soon. It could have something

to do with gender stereotypes and the male ego, but I like to think

that our society is past that at this point. Honestly, I feel it

could be something as simple and shallow as the cover art and design

of the novels.

The reason this concerns me so much is that the

literary trend, especially with Young Adult fiction, is gravitating

more and more towards using female narrators and protagonists. If

this trend continues, and if men continue to be repelled by female

main characters, men are going to stop reading altogether. Okay, so

maybe this is a slight exaggeration, but I fully believe that there

will be a swift decline in the number of male fiction readers if

these trends continue.

There’s probably no easy way to answer any of

these questions and, as I said, we will probably not come to any

clear conclusions any time soon. However, I believe that talking

about it and drawing attention to it, not only as readers, but as

English majors, as future teachers, publishers and writers, is the

first step we have to take to, if not remedy, at least understand

this situation.

Survey Says!!!!

"Who Is Your Favorite Female Character In

Literature?"

Janie in Zora Neale Hurston's

Their Eyes Were

Watching God

She grew into such a beautiful being on the inside as well as

the out and found a way to stand on her own two feet without the

assistance or need for approval from others.

She's my she-ro.

- Fannetta Jones

My

favorite female character in literature is Jane Eyre from

Charlotte Bronte's book Jane Eyre. I like her because she is

an intelligent and driven young woman who is more admired

for her personality than her beauty. Also she stands up for

herself and speaks her mind. My

favorite female character in literature is Jane Eyre from

Charlotte Bronte's book Jane Eyre. I like her because she is

an intelligent and driven young woman who is more admired

for her personality than her beauty. Also she stands up for

herself and speaks her mind.

-Katie Struck

"Molly Millions," from

Neuromancer and Other

Works by William Gibson.

-Alex Kane

Briony Tallis from Ian McEwan's Atonement.

What can I say, I like the evil ones.

Briony Tallis from Ian McEwan's Atonement.

What can I say, I like the evil ones.

-Melissa Bankes

Scout, from

To Kill a

Mockingbird.

-Brandon T. Groom

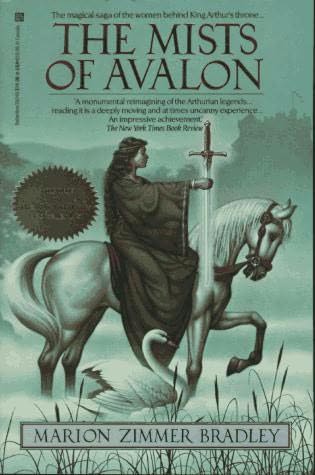

Guinevere is my

favorite female character in literature.

-Robert Cook

|

Hm.

There are so many to choose from! But, I'd probably have to pick

Luna Lovegood from the Harry Potter series. I think she's not

only goofy and hilarious, but super smart and wise beyond her

years. She's just all-around amazing. In a book series full of

awesome male characters (Snape, Sirius, Lupin) she really

shines.

Hm.

There are so many to choose from! But, I'd probably have to pick

Luna Lovegood from the Harry Potter series. I think she's not

only goofy and hilarious, but super smart and wise beyond her

years. She's just all-around amazing. In a book series full of

awesome male characters (Snape, Sirius, Lupin) she really

shines.

-Alex

Nall

-Alex

Nall