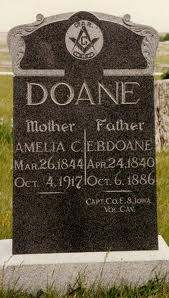

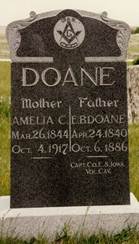

E.B. DOANE

PATRIOT, PIONEER

By William Urban

1970, 2011

FOREWORD

The writing of any biography involves luck, hard work, travel, research, and

the help of many people. This biography was no different. The letters on

which it is based were loaned to me by Leslie Doane, who had been given them

because he and E.B. Doane had shared the experience of being a

prisoner-of-war, he at Bataan. I sought out further documentary evidence

from the National Archives, the Iowa Yearly Meeting of the Society of

Friends, the Iowa State Historical Society, the Kansas Historical Society,

several local Iowa and Kansas libraries, and the Monmouth College Library.

Also I received much assistance from my Doane relatives.

It has been possible for me to visit the sites of E.B. Doane’s activity in

Iowa and Kansas, and to follow his routes across Missouri and Arkansas, and

Tennessee, Georgia, and South Carolina. Living close to Iowa, and having

relatives in Kansas, these visits were more than just cursory, and made the

writing of the biography much more enjoyable.

It should be noted that the name Eleazar has various spellings. Eleazer and

Eleazor are most common. The King James version of the Bible spells it

El-a’-zär (Eleazar and Ithamar are the surviving sons of Aaron; see

Leviticus 10), but E.B. Doane

spelled his name, and his family name as well, in various ways and preferred

to be called E.B. or Captain Doane.

William L. Urban

Lee L. Morgan Professor

of History and International Studies

Monmouth College, Monmouth

IL

ELEAZAR BALES DOANE: PATRIOT, PIONEER

That numerous descendants of the Doane

family are to be found in north central Kansas today in only a reflection of a

wider movement of Quaker pioneers over a period of many years. The original

settlement in Pennsylvania saw a Daniel Doane migrate there from Massachusetts,

then, being dissatisfied with the insistence that he abandon his interest in

astronomy, moved to North Carolina; Jesse Doane, finding that his abolitionist

views were unwelcome, moved with other Quakers to a settlement near Knoxville;

Robert Doane moved to Indiana, then to Iowa; finally E.B. Doane emigrated to

Kansas, there to leave his Quaker faith for lack of fellow co-religionists. This

background of pioneer ancestry with a deep commitment to a difficult faith

explains much about the central figure of this investigation, Eleazar Bales

Doane.

Eleazar Bales Doane lived in a crisis moment in American history. The

movement west and the conflict over slavery were at their height, and he was

involved in both. As America grew, and changed, and suffered, he grew, and

changed, and suffered with her.

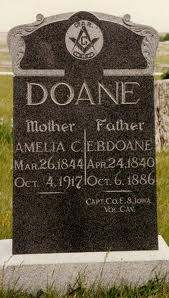

Eleazar Bales Doane was born in Morgan

County, Indiana, April 24, 1840, in a frontier community of Quakers. His father,

Robert, had come to Indiana with friends and relatives at the age of

twenty-three and leased a farm. Two years later, on June 12, 1839, Robert

married his cousin, Rachel Doane. Eleazar was the eldest child of seven, but

only four survived infancy: Eleazar (1840), Ithamar (1841), David (1847), and

Mary (1849). The names chosen for the children illustrate the parents’ deep

knowledge of and respect for the Bible, an attitude they passed in to the

children.

Eleazar’s memory of Indiana was to be dim, however, because pioneers were

always eager to be on the move westward, and his family was in the pioneer

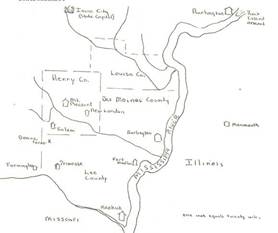

tradition. In 1847 His parents migrated to southeastern Iowa, where large

numbers of Quakers were settling around the town of Salem. Robert Doane set out

alone, first purchasing land in Cedar township of Lee County, building a log

cabin, and then putting in his first crop. Afterwards he sent for his family.

Thus it was that the Doanes came to

Iowa. It was a good land, but untamed, and life was primitive. In 1850, when

Eleazar was but ten years old, an eastern Quaker described it:

The residences of the settlers in this place, scattered over the prairie land,

are chiefly log buildings; the settlement being several miles in extent. In the

summer season, while the grass is green, the country, with the cabins and little

surrounding improvements dotted over it, has a picturesque appearance; yet to

the stranger it gives a sensation of lonesomeness.

Eleazar was young, but in those

days everyone worked, and the eldest son of a pioneer family undoubtedly had

many chores thrust upon him. While his father worked the two hundred and twelve

acre farm, Eleazar probably assisted his mother in caring for the animals and

the garden. Later he would work in the fields. There being but a year’s

difference in age, his brother Ithamar was probably a constant companion in work

and play, and a firm friendship bound them together. Unhappily, in 1852, when

Eleazar was twelve, his mother and his infant sister died. His life was greatly

affected by this tragedy.

Robert

Doane accepted the loss of his wife and help-mate. On the frontier there was

little time to mourn. Life was hard, and many died young. The survivors had work

to do, and Eleazar’s father devoted himself to the rearing of his four young

children. He never remarried. He never traveled much. But he built a model farm,

with a fine house and barn. And he was a well-read man, deeply versed in the

Bible and the classics. He was interested in politics, and was undoubtedly an

early member of the Republican party. And he brought up his family to be

likewise involved in important ideas and issues.

Robert

Doane accepted the loss of his wife and help-mate. On the frontier there was

little time to mourn. Life was hard, and many died young. The survivors had work

to do, and Eleazar’s father devoted himself to the rearing of his four young

children. He never remarried. He never traveled much. But he built a model farm,

with a fine house and barn. And he was a well-read man, deeply versed in the

Bible and the classics. He was interested in politics, and was undoubtedly an

early member of the Republican party. And he brought up his family to be

likewise involved in important ideas and issues.

Robert Doane was not, however, what Quakers call a “weighty Friend.” He

had been disowned by White Lick Monthly Meeting in Indiana before his removal to

Iowa, and now his farm lay several miles from the Meeting House in Salem,

separated by a creek bed impassible in bad weather. It was a difficult enough

journey in good times, and Robert had much work to make his farm support his

family. Apparently he and Rachel had notified the Salem Meeting of their

intention to unite in membership there in 1851, but Robert submitted his request

that he and his minor children (David, Mary and Sarah Elizabeth, who had died in

April) be united with Salem Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends. This

request was discussed at length by the membership. At that time in Quaker

history, Friends were much concerned with maintaining their purity, which meant

separation from the “world’s people.” Quakers were extremely strict Christians.

They wore the plain clothing, used the plain talk, and pursued lives of utmost

simplicity and piety. They disowned members for “marrying out of unity with

Friends,” cursing, going to court, dancing, participating in military

activities, and other “worldly” activities. They held strong positive

testimonies as well, taking unpopular stands against human slavery and for fair

treatment of the Indians. If one did not measure up to these testimonies in

every way, it did not mean that one was not an exemplary Christian by other,

more conventional standards. Furthermore, there was a schism among Iowa Friends

were demanding a more militant stand on the question of Abolition. As early as

1845 numbers of these Friends had felt constrained to withdraw from Salem

Monthly Meeting over this issue and, although many reunited with Salem Monthly

Meeting in succeeding years, antagonism still remained.

Robert Doane was not, however, what Quakers call a “weighty Friend.” He

had been disowned by White Lick Monthly Meeting in Indiana before his removal to

Iowa, and now his farm lay several miles from the Meeting House in Salem,

separated by a creek bed impassible in bad weather. It was a difficult enough

journey in good times, and Robert had much work to make his farm support his

family. Apparently he and Rachel had notified the Salem Meeting of their

intention to unite in membership there in 1851, but Robert submitted his request

that he and his minor children (David, Mary and Sarah Elizabeth, who had died in

April) be united with Salem Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends. This

request was discussed at length by the membership. At that time in Quaker

history, Friends were much concerned with maintaining their purity, which meant

separation from the “world’s people.” Quakers were extremely strict Christians.

They wore the plain clothing, used the plain talk, and pursued lives of utmost

simplicity and piety. They disowned members for “marrying out of unity with

Friends,” cursing, going to court, dancing, participating in military

activities, and other “worldly” activities. They held strong positive

testimonies as well, taking unpopular stands against human slavery and for fair

treatment of the Indians. If one did not measure up to these testimonies in

every way, it did not mean that one was not an exemplary Christian by other,

more conventional standards. Furthermore, there was a schism among Iowa Friends

were demanding a more militant stand on the question of Abolition. As early as

1845 numbers of these Friends had felt constrained to withdraw from Salem

Monthly Meeting over this issue and, although many reunited with Salem Monthly

Meeting in succeeding years, antagonism still remained.

Since Robert Doane seems to have adhered to this abolitionist party (or,

at least, to its principles), the reluctance of Salem Friends to admit him to

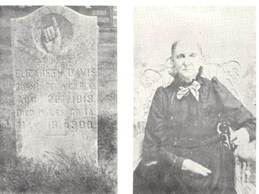

membership is understandable. Indeed, Rachel Doane was buried in the Friends’

burial ground held by the Anti-slavery Meeting until 1862, when it was sold to

Salem Meeting. When Robert Doane and his minor children were finally united with

Salem Monthly Meeting, the

resulting ties were not close. The occasion of their admittance into membership

was also the last time that these Doanes were mentioned in the minutes of the

Monthly Meeting.

Perhaps they were among that group the answer to the Queries castigated: “there

is a manifest lack in others in so frequently neglecting the attendance of our

religious Meeting.

Nevertheless, there were preparatory Meetings closer to Robert Doane’s residence

and he did retain his membership in the Society of Friends to his death in 1889.

Always he was known as a devout and well-educated man, and he gave his children

a firm knowledge of the Bible and other religious works.

Eleazar’s

maternal grandparents, David and Ruth Doane, farmed one hundred and sixty acres

not far away. As a young man David had worked wherever he could to support his

family, but could not afford a farm until he emigrated to Iowa in 1848. By the

time of his death in 1862 he had become moderately prosperous.

David was not a model Friend either. Early in 1852 he was disowned by Salem

Meeting “for using unbecoming language,” and reunited only in 1858.

Eleazar’s

maternal grandparents, David and Ruth Doane, farmed one hundred and sixty acres

not far away. As a young man David had worked wherever he could to support his

family, but could not afford a farm until he emigrated to Iowa in 1848. By the

time of his death in 1862 he had become moderately prosperous.

David was not a model Friend either. Early in 1852 he was disowned by Salem

Meeting “for using unbecoming language,” and reunited only in 1858.

It is of some interest that young

Eleazar and Ithamar did not request membership in Salem Meeting. Although they

shared many of the testimonies common to Friends, they did not share the

adversion to warCthey

were willing to participate in that evil in order to eliminate a greater one,

human slavery. Certainly, although Eleazar received good religious training, he

was never closely associated with the Society of Friends in a formal capacity

and apparently frequented the social activities at nearby Sharon Presbyterian

Church. However, he was deeply beholden to Friends for their strong testimony

against slavery and their independence of spirit.

Slavery was the central and crucial

question of that era. Much earlier, when William Penn invited the German

settlers into Pennsylvania, the new immigrants asked how slavery was to be

reconciled with the Golden Rule. Friends became concerned and opposition to

slavery was a widely accepted testimony before the Revolutionary War. All

Eleazar’s Quaker ancestors shared this attitude. A great-grandfather left the

North Carolina because of hatred for slavery, and many Doanes were active in the

underground railroad in Indiana. Salem, Iowa, was a hotbed of Abolitionist

activity. Some Quakers there formed one of the four quarterly meetings of the

Indiana Yearly Meeting of Anti-Slavery Friends, and they made Salem into a major

center for the underground railroad, smuggling escaped slaves out of Missouri

into Canada. For obvious reasons, participation in such illegal activities was

kept secret, but it is quite likely that the Doanes assisted in violations of

the Fugitive Slave Act.

Their farm lay on the road from Missouri to Salem.

Eleazar’s education emphasized the

importance of the slavery issue. Among the first settlers of Salem was a

prominent anti-slavery Quaker educator who founded a school in that settlement.

Unfortunately, he died shortly afterward; however, he left behind a tradition

that led to the foundation of a short-lived college in Salem.

Ten miles to the north, in Mount Pleasant, a noted Abolitionist named Samuel

Luke Howe opened a High School for boys and an Academy for girls. His

newspapers, the Iowa Freeman and the Iowa True Democrat, strongly

opposed the Compromise of 1850 and all subsequent acts which tended to keep

slavery alive. Howe was in Kansas in 1856, helping Free Soilers defend Lawrence

against the Border Ruffians from Missouri, and often thereafter he was in the

company of John Brown. Though variously called a “madman, fanatic, and

agitator,” he was an influential figure. General Sherman, his pupil in Ohio,

later wrote: “Prof. Howe I consider to be the best teacher in the United

States.” Another former student wrote: “The students in Prof. Howe’s school drew

in Abolitionism with their Latin and their mathematics....To the end of their

lives will his students to be proud to admit the molding influence of that

mastermind.”

Eleazar Doane studied under Samuel Luke Howe.

This anti-slavery attitude was widely

held among Iowans in general, but often for very different reasons. Many workers

feared that the extension of slavery would lower wages. These hated and feared

even the Free Negroes, because Negroes would work wherever they could for

whatever wages they could obtain. Therefore, some whites sought not only to

eliminate slavery, but also to eliminate the Negro. Others saw slavery as a

threat to democracy. Only the rich could afford slaves, and in the South

plantation owners appeared to have disproportionate political influence. Iowans,

being largely yeoman farmers, hated slavery for the economic, political, and

social threat it represented. As early as 1854 the Whig candidate for governor

was elected on an anti-slavery platform. That same year the Republican party,

and even its candidate for President in 1860, Abraham Lincoln, was not an

Abolition party. In fact, Republican leaders were careful to emphasize that

their party did not advocate Abolition, but only opposed the extension of

slavery into the territories.

Eleazar Doane, a young man approaching

maturity in these turbulent years, had opportunity to participate in these

exciting political developments. Nearby in Illinois, within a day’s ride,

Lincoln and Douglas debated. In Iowa, pro- and anti-slavery orators spoke before

large audiences, and the ready communications afforded by the Mississippi River

kept Iowans informed as to public opinion in Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee,

Arkansas, and Missouri, areas where talk of secession was becoming increasing

serious. The Democratic party was badly divided; the Whig party was dying; and

thus the Republican party became the party of Union, the party of patriotism.

Eleazar Doane was undoubtedly a Republican from the beginning, for that party

endorsed unity and opposed slavery.

Therefore, when war broke out between

the North and the South in 1861, Eleazar Doane and his family were deeply

concerned. Not backward in any way, he attempted to enlist immediately. His

declaration read:

I, Eleazar Doane, desiring to enlist in the army of the United States for the

period of three years and 5 months of age, that I have never been discharged

from the United States service on account of disability, or by sentence of

court-martial, or by order before the expiration of a term of enlistment, and I

know of no impediment to my serving honestly and faithfully as a soldier for

three years or during the present war.

Witness W. W. Woods ELEAZAR

DOANE

I, Eleazar B. Doane do solemnly swear, that I will true allegiance to the United

States of America; and that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against

all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and observe and obey the orders of the

President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over

me, according to the rules and articles for the government of the armies of the

United States.

ELEAZAR B. DOANE

State of Iowa Des Moines County

Burlington Township

Subscribed and sworn

to before me by the said Eleazar B.

Doane

this 23rd day of September, A.D. 1861

5 ft. 7 in. high, light

Geo. Sampler,

complexion, hazel eyes, light

Justice of the Peace.

brown hair, and sandy whiskers,

Des Moines County, Iowa.

residence Cedar Ts.

Lee County, Iowa.

But Eleazar’s enlistment was not

accepted. The Iowa enlistment was filled to the legal limits, and the surplus

volunteers were told to wait; perhaps they would yet be needed. So he returned

to teaching. Probably he and his family hoped for a quick Union victory. Avid

readers, they followed the course of events through the local newspapers,

especially the Weekly Gate City, an abolitionist paper from Keokuk.

Most persons in the North believed that

the South would be overwhelmed in a few weeks, but the Battle of Bull Run

snuffed their hopes for an easy victory. As the North began to raise a larger

force for another invasion of Virginia, the South also used this time to train

new troops, so that when General McClellan moved south again in the summer of

1862, Lee was able to check him at the Seven Days Battlefield. It then became

obvious that a national effort was needed, and on July 2nd, 1862, President

Lincoln asked for 300,000 volunteers.

Within a fortnight Iowa’s Republican

governor issued a proclamation:”The time has come when men must make, as many

have already made, sacrifices of ease, comfort, and business for the cause of

the country.”

The anti-war agitation of Vallandingham and other Democrats was overwhelmed by

Republican editorials such as this one in the Burlington Hawkeye:

THERE IS A WAR—Little by little, day by day, the country is finding out there is

a war going on. For fifteen months armies have been in the field...But the great

mass of the people have not yet realized the gigantic importance of the

contest...The time seems to have come for greater exertion—a more thorough

awakening and a deeper determination.

Eleazar Doane had made his decision

earlier, and now that Iowans were authorized to raise twenty-two regiments,

Eleazar Doane and his brother Ithamar enlisted in the first of the volunteer

units to form, the 19th Iowa Infantry, which mobilized in August in

Keokuk.

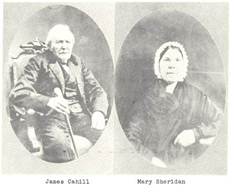

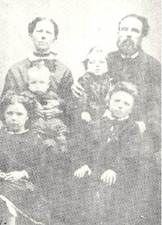

Eleazar

Doane gave up much to enlist. His farming and his teaching could wait, but would

a young lady named Amelia Cahill? She had come to Iowa with her mother, sister,

and step-father, and resided in Harrison township of Lee County, just south of

the Doane farm in Cedar Township.

Her brother had remained in Cincinnati to be reared in their grandfather’s

strict Irish Catholic home, but Amelia and Mary Jane apparently attended

services at Sharon Presbyterian Church (although their names do not appear on

the poorly-kept membership lists there). Amelia was just eighteen, and would

soon begin to teach school at nearby Primrose and Farmington. Perhaps she

promised to write to the young warrior. That was not uncommon and, to be sure,

some young ladies wrote to so many acquaintances in the army as to cause a local

scandal.

Eleazar

Doane gave up much to enlist. His farming and his teaching could wait, but would

a young lady named Amelia Cahill? She had come to Iowa with her mother, sister,

and step-father, and resided in Harrison township of Lee County, just south of

the Doane farm in Cedar Township.

Her brother had remained in Cincinnati to be reared in their grandfather’s

strict Irish Catholic home, but Amelia and Mary Jane apparently attended

services at Sharon Presbyterian Church (although their names do not appear on

the poorly-kept membership lists there). Amelia was just eighteen, and would

soon begin to teach school at nearby Primrose and Farmington. Perhaps she

promised to write to the young warrior. That was not uncommon and, to be sure,

some young ladies wrote to so many acquaintances in the army as to cause a local

scandal.

Eleazar Doane was so determined to enlist that he left his farm, his schooling,

and his romantic interests behind and went to war with a number of his Henry

County friends. One of these was Richard Root, a capable surveyor and scout of

some thirty years of age. He had spent several years in the Rockies, apparently

for adventure, and returned to Iowa to enlist as Lieutenant. Another was W.I.

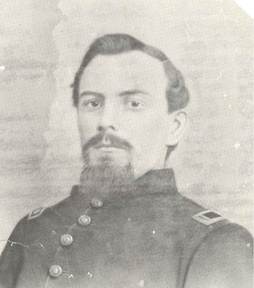

Babb, made Hospital Steward of the 2nd Battalion because of his more advanced

education. Ithamar Doane, because of his education and connection with Prof.

Howe, perhaps because of his firmly expressed beliefs, was made 2nd Sergeant of

Captain Roderick’s Company. At this time Eleazar abandoned his cumbersome given

name and called himself simply E. B. Doane.

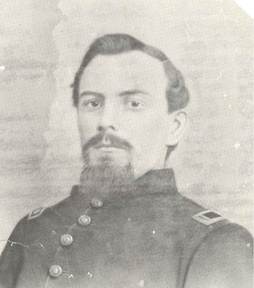

An intense, serious young man, E.B. went

to fight for his conviction that slavery was wrong and Union was right.

Twenty-two years of age, 2nd Sergeant of Captain Roderick’s company, he was very

patriotic, but interestingly enough, he accepted the twenty-five dollar bounty

for enlistment, and collected the two dollar bounty for bringing in an

enlistment!

The 19th Iowa Volunteer

Infantry was mustered in September 3rd, 1862. The Editor of the Keokuk paper

reported:

DRESS PARADE. B. Crabb, Colonel, and G.G. Bennett, Adjutant of the 19th

regiment arrived in town yesterday morning. They visited the camp during the

day, and in the evening officiated at the dress parade, when the Colonel made a

short speech, and complemented the men on their fine appearance, and expressed

the ardent hope that the 19th might be the best regiment that ever

left the State. The Colonel may well be proud of his men. It is generally

remarked that a regiment of better men has not appeared in this city.

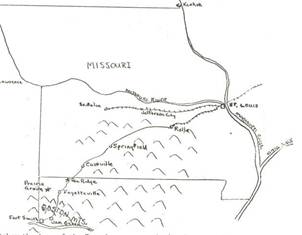

Three months after his

enlistment and two weeks after muster, E. B. Doane and the 19th Iowa

Infantry were shipped by river to St. Louis.

Fortunately for the men of the 19th Iowa, they remained at the

disease-ridden Benton Barracks less than a week before proceeding to Rolla,

Missouri. Probably they traveled south on the South West Branch Pacific

Railroad. If so, they were spared marching through interminable miles of rolling

red Missouri hills covered with scrub forests of small oaks and maples. But the

railroad ended at Rolla, and as many miles lay ahead of them as lay behind. They

transversed nother one hundred and fifty miles of uninhabited and useless Ozark

mountains, red and dry, by September 25th. As the forest opened to reveal the

beautiful valleys and fields of this corner of Missouri and Arkansas, the troops

must have breathed sighs of relief. The beauties of the Ozarks in early autumn

were, after all, the announcement of the annual death of nature, a reflection

congenial to that generation of mankind (and hardly to console soldiers fresh in

the field), and the barren mountains possibly concealed hostile armies.

Fortunately for the men of the 19th Iowa, they remained at the

disease-ridden Benton Barracks less than a week before proceeding to Rolla,

Missouri. Probably they traveled south on the South West Branch Pacific

Railroad. If so, they were spared marching through interminable miles of rolling

red Missouri hills covered with scrub forests of small oaks and maples. But the

railroad ended at Rolla, and as many miles lay ahead of them as lay behind. They

transversed nother one hundred and fifty miles of uninhabited and useless Ozark

mountains, red and dry, by September 25th. As the forest opened to reveal the

beautiful valleys and fields of this corner of Missouri and Arkansas, the troops

must have breathed sighs of relief. The beauties of the Ozarks in early autumn

were, after all, the announcement of the annual death of nature, a reflection

congenial to that generation of mankind (and hardly to console soldiers fresh in

the field), and the barren mountains possibly concealed hostile armies.

Springfield was a bustling young city,

the key to the southwestern frontier. The second battle of the war had been

fought here, to save Missouri for the Union. The 19th Iowa was

assigned to construct fortifications and to act as prison guards. These duties

were necessary, but amid these activities, combat training was somewhat

neglected.

The Iowans were to learn from experience.

In October the Army of the

Frontier was organized under General Herron with the duty of protecting the

western states from southern invasion and of occupying as much rebel territory

as possible. General Herron gave orders to march south. The weather was wet,

windy, and cold, the worst possible for a campaign in the Ozark mountains.

The first difficulty arose

at the Arkansas line. The Missouri militia units refused to march further south,

saying that they had enlisted for service in their own state only. The 20th

Wisconsin fixed bayonets and the 19th Iowa took up a position in the

rear of the militia and “the militia were given to understand they would have a

more relentless foe in their rear than front, if they refused to do their duty.”

A young member of the 19th described the march into Arkansas:

Our division then moved west into Benton County, Arkansas, and encamped on Sugar

Creek, to the right of Pea Ridge battle ground... Here we remained two days,

when, on Monday evening at dusk, October 20th, we again took up our line of

march. Slowly we moved out, at first on the main road, then bearing southwardly

until we struck the battle ground of Pea Ridge, which we crossed in silence at

midnight. Making a short pause at Elk Horn Tavern, (now rendered historic from

its location on the battlefield), we pushed on southeast, halting and resting an

hour before day-light, and then resuming the line of march. All day we pushed

our way down through the ravines and finally up a spur of the Ozark camps on the

banks of the White River. We had marched all night and all day without anything

to eat, and you may well imagine our appetites were keen. But you may take my

remark about “pitching camp,” as purely “sarcastical.” Not a tent was allowed to

be taken from the wagons, and only one hour in which to get supper and prepare a

day’s rations for the morrow. Of course, it was all that could possibly be done

to get enough cooked for our suppers. We then fell into line, an hour or two

after dark, marched down to the river, which was quite swift and deep, partly

stripped ourselves and forded it—It was a cold bath, but the men took it without

a word of complaint. It was a scene for an Artist’s pencil—that crossing the

White River at night. A huge fire on the opposite bank cast a glare over the

water, and lighted up the faces and bare limbs and glistening guns of the

soldiers, as with many a laugh and shout they stumbled their way across. Once

all over, large fires were built up, and from midnight till 4 o’clock we

shivered and slept around them. An hour then for breakfast, and just as day

began to break, we were on the way. Another long day’s march over rocky spurs

and down long ravines, where gurgling springs rushed out from the rocks to

refresh us, but with nary a sign of welcome from human face... An hour before

dark we stopped, got a hasty supper, and then, to the surprise of the army,

instead of going on to Huntsville, which we were near, we filled to the right

and marched hastily west. On we went, now pausing while the cavalry dashed to

the front, or to open the way for our battery wagons, occasionally making a

short halt for rest. About 2 o’clock at night we reached White River again, and

then rested till 5. This gave a chance for our trains to get up, and for the

poor, foot-sore, tired and worn out stragglers from the column also to catch up.

At daylight we started on without anything to eat, crossed the river again,

ascended the hill, and word came that the Rebels were several thousand strong a

few miles in front. A march of nearly ten miles, much of the way on

double-quick, brought us to the main road from Elk Horn to Fayetteville, about

13 miles below the former place. Here we were drawn up in line of battle—the 19th

Iowa on the left and the 20th Wisconsin on the right of our battery,

while the gallant 1st Calvary led a dashing charge down the road three or four

miles, scattering the rebels and causing them to make exceedingly fast time

toward Fayetteville...I venture to assert that no regiment from Iowa has done

more hard marching than we of the 19th, for the time we have been in

service. To resume, we marched three days and the greater part of three nights,

over the roughest roads in America, with only three hastily prepared meals

during the whole time—72 hours—and traveling upwards of a hundred miles.

Another volunteer wrote:

The 19th Iowa Infantry left Rolla, Mo. on the 16th say of

September, and since that time have marched 370 miles over mountainous

country...The 19th is a fine regiment of men, but to use them up in

this God-forsaken country by such marches and countermarches as they have been

performing is indeed a pity.

And it got worse, not better. It rained

for days on end, and the roads almost disappeared in mud. The baggage trains

were left far behind, the supplies did not arrive on time, and many nights were

spent cold, wet, and hungry with only the expectation of continuing the march

the next dreary morning.

On December 6, 1862, the Army of the

Frontier was a few miles southwest of Fayetteville, Arkansas, after a march of

one hundred and ten miles in three days through mountainous and heavily forested

country. As the long columns of troops neared the river, scouts saw Confederate

entrenchments covering a ridge on the opposite bank. General Herron drew away

the defenders’ attention with a feint and audaciously crossed the river and

formed his army opposite the enemy. Only then did the danger of the situation

become apparent. The Confederate force was four times the size of the attackers,

and the nearest Union brigade was ten miles distant. Nevertheless, relying on

his initiative, General Herron ordered an attack by the 19th Iowa and

the 20th Wisconsin. Ingersoll described the attack:

It was a grand sight. The batteries advances across the open field, belching

forth and smoke, and sending shell, and grape, and canister into the woods in

front as they moved up, and gallantly supported by the Nineteenth Iowa,

Lieutenant-Colonel McFarland, and the Twentieth Wisconsin. A rebel battery near

the edge of the hill, and a heavy force of infantry constantly fired on the

audacious brigade, thinning its ranks at every volley, but it pressed on

steadily and firmly till within a hundred paces of the base of the hill. There

the artillery halted and the infantry dashed ahead in one of the bravest charges

ever made. Moving across the rest of the open field with bayonets fixed, the

brave men of the Nineteenth Iowa and Twentieth Wisconsin rushed up the hill,

drove the infantry support from the battery, captured the guns, and moved on

against the enemy higher up the hill. Overpowered by numbers they were driven

back; but rallying under the cheering voice of McFarland they again attempted to

carry the position, but were again overwhelmed by numbers and compelled to

retire, but not till the undaunted McFarland and hundreds of his gallant

comrades had fallen on that fatal field. It was as brave a fight as men ever

made, but here it did not avail.

The battle raged back and forth all day.

Union reinforcement saved the army from disaster, and nightfall brought an end

to the carnage. In the dark the Confederates, still outnumbering the Union

forces three to one, slipped away, leaving over one thousand bodies on the

battlefield. In the morning the Unionists counted over one thousand casualties

of their own, of whom one hundred and eighty-seven were dead. E.B. Doane’s

Company was hard hit, and his brother Ithamar was wounded in the shoulder.

Official reports were enthusiastic:

I cannot speak too highly of the gallant conduct of the officers and men of the

Nineteenth Iowa, for after being repulsed with great loss by an overwhelming

force of the enemy, they rallied and brought from the field the colors of the

Twentieth Wisconsin Regiment. Captain (S.F.) Roderick, of the Nineteenth Iowa,

deserves special mention for his meritorious conduct. He gathered together some

70 men of his regiment, after it was broken and scattered; rallied them around

the regimental colors, and, under my direction, formed them to the left of the

Ninety-fourth Illinois, where they did good service, and only retired from the

field when ordered to fall back. Lieut. Richard Root, acting adjutant of the

regiment, is also entitled to honorable mention. By direction of his commanding

officer, and at the request of his captains, he took command of three companies

of skirmishers, and maneuvered them with great bravery and skill.

It can be assumed that E.B. Doane

fought under his immediate superior, Lieut. Root.

Once recovered from the fighting, the 19th

Iowa resumed the advance. E.B. Doane was with the regiment December 28th,

when it captured Van Buren, Arkansas.

The Confederates had hoped that the mountains themselves would defend this

highly strategic point where the Arkansas River breaks into the Ozarks right on

the edge of the Indian Territory. It controlled the route from southwest

Missouri into Texas and access to the Indians, whose alliance was desired by

both North and South. But in a long night march the 19th Iowa crossed

the rugged Boston Mountains and occupied Van Buren. By the 31st the

unit had returned to Prairie Grove, where Gen. Schofield reviewed the troops on

January 2nd.

On January 3, 1863, Sergeant E.B. Doane

was detached from Co. K of the 19th Iowa infantry on recruiting duty,

and returned to Iowa in company with his friend and commander, Lt. Richard Root.

They reported to Capt. Hendershot, the Superintendent of the Recruiting Service

in Iowa, and were assigned to a small town in Henry County, New London. They set

up their recruiting station in Perry Frank’s Boot and Shoe Store, but presumably

they also traveled around seeking out enlistees. They advertised:

Best and Bravest Regiment in the Field...

One months pay and $25 of the $100 in advance.

Anyone bringing in a recruit will receive a premium of two dollars.

In May they were reassigned by

the new Superintendent to Mount Pleasant, where they established their post in

the Brazelton House.

Without doubt, recruiting

duty allowed both men opportunity to visit friends and family, and even to do

some “sparking.” E.B. Doane took advantage of his opportunities. He must have

made many trips down into Lee County to court Miss Amelia Cahill. Certainly, on

the Fourth of July he escorted Amelia to the Independence Day Celebration. This

was traditionally the biggest holiday of the year, and the war made it even

larger. Everyone went to the Fair. And that evening she accepted his offer of

marriage.

However, marriage had to

wait. When Lt. Root and Sergeant Doane were offered commissions in a new cavalry

unit being formed, they accepted with alacrity. Soon thereafter, on August 1st,

Special Order 105 discharged them from the 19th Iowa so they could

concentrate on recruiting men. Already they had signed up a number of men from

Henry County, the first on July 4th; now Captain Root and First

Lieutenant Doane hurried to fill the ranks of Company E, 8th Iowa

Volunteer Cavalry.

As commander of this new

regiment the Secretary of War chose Lieutenant Joseph B. Dorr. Dorr had been a

noted Democratic editor in Dubuque, and in the presidential campaign of 1860

Stephen Douglas had written the “Dorr Letter” to him. He had volunteered for the

first units organized, had accepted a minor commission, fought bravely at

Shiloh, and escaped from prison camp. So many volunteers flocked to join his

unit that many had to be sent to other regiments. Many veterans such as E.B.

Doane were advanced to officer rank, and new equipment issued, so that the 8th

Iowa was considered one of the finest regiments ever raised in the state.

It was not long before he wrote home:

Dear Father, Brother, and Sister,

I arrived here safe this morning. Everything is all right. The order to muster

me out for Promotion has come from the war department and I will probably be

mustered out tomorrow. I was ordered to take command of the company this

morning. Mendenhall has been thrown out and Charles Sanderson from Keokuk of the

9th Iowa Infantry is 2nd Lieut. of the Co. Lieut. Anderson is acting

Adjutant of the Regt and I have all the Responsibility of the Co. to face alone.

Capt. Root is here but can’t take command yet. But will soon take the command of

a Battalion as Major. The Boys are mostly well, none in the hospital. Orderly

Durham I understand he is pretty sick. I haven’t seen him yet.

Father I want you to take charge of my corn and I hereby authorize you to do so

and to sell it. Do just whatever you think best under the circumstances. If the

affair can be settled honorably by letting P. John have the corn, all

right, and if he attempts to make trouble about it, I want you to enter suit

against him for the corn he has taken and Garnish the money in King’s hands for

the pay or the corn and the maintenance of the suit. But if he will come up and

act the man and do me justice, give him a chance and if not take the start of

him in the suit. See King and so the best you can and see that Patterson gets

the money that I failed to get in Salem. If it can’t be had there in a week

write and let me know and I will send it down from here. Write soon and let me

know how things are prospering about that corn. Prince is all right. I got along

finely with him on the Boat. He made friends of all the sick hands on the Boat.

No more at Present, but remain as ever yours.

E.B. Doane.

This letter indicates that

young Lieutenant Doane was very much a man of his era—eager, ambitious, somewhat

quarrelsome, and sentimental, particularly over his horse, who was a pet, not a

beast of burden. His proposed lawsuit further shows how little Quaker principles

affected him—Friends did not enter suits at law.

The regiment was mustered

at Camp Hendershott in Davenport on September 30, 1863, and transported to

Louisville, Kentucky, on October 17-21. It was his first experience in command

of a company. Capt. Root was absent Oct. 16-31st, and E.B. Doane replaced him

without difficulties of any kind.

On November 4th the 8th Iowa

began the march south to Nashville, a journey of almost two weeks through

country badly devastated by war.

They were to escort a heavy forage train and the First Kansas battery (old

comrades-in-arms from Prairie Grove battlefield). All were in fine spirits.

Indeed, some had too many spirits and were more than mildly intoxicated. As it

happened, the Quartermaster of the 8th Iowa become a little drowsy

and decide to take a short nap just off the road. Unfortunately for him, he did

not awake before the last wagons and the rear guard had passed far down the

dusty road. His first sight on regaining his faculties was of a tough and ragged

group of Confederate guerrillas who had been trailing the Union force and had

spotted him dozing in the grass. They stripped him of weapons and clothing,

brought out a rope and threatened to hang him unless he told them about the

unit’s strength and destination. After he told them what they wanted, they

turned him loose, naked and horseless, to make his way to the camp. Captain Root

joked, “We had quite a gay time over his returning in the plight he was.”

Later, some persons objected to the veracity of this account, but Captain Root

affirmed that it was the truth, and accompanied his letter with an affidavit

signed by several officers, among whom was E.B. Doane.

Late in November the unit received its carbines,

so the men expected to join the main army immediately. Instead, the 8th

Iowa was assigned to guard the communication lines west of Nashville. This was

an important and dangerous duty, but hardly glamorous. Without doubt, the men

grumbled. Wars, however, are not won by raw courage alone. Food, ammunition,

medicine must be available to the troops at all times and in spite of all

difficulties. Hundreds of thousands of men labored to bring supplies to the

battlefront. Every case of biscuits, every canister of shot was loaded and

unloaded onto a succession of wagons, steamers, trains and mules until it

arrived at its destination hundreds of miles away, perhaps unusable because of

mishandling somewhere along the line. The problem of bringing supplies to the

Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga was almost insuperable. Major battles had

been fought at Shiloh and Corinth to occupy the lower reaches of the Tennessee

River, but farther up it remained closed to steamers. That left the rail line,

which was fairly safe south of Nashville, thanks to the large numbers of Union

troops; to the north, however, on the Louisville and Nashville R. R.,

Confederate guerrilla forces had almost halted traffic. That would not be

serious if the Cumberland River had been navigable year around, but low water

made the Harpeth shoals and other points impassible. If the army at Chattanooga

was to be supplied, a new route had to be opened. Army engineers chose to finish

a spur of the Memphis-Nashville railroad from Nashville to Waverly and add a

short to a landing on the Tennessee River at Johnsonville. This allowed supplies

to be shipped from Paducah to Johnsonville by steamer, and then loaded onto

trains and sent to the great arsenals at Nashville for trans-shipment south. Of

course, this attracted Confederate attention. When guerrillas and even regular

Rebel units began to raid the line, the Eighth Iowa was stationed there to

protect it.

Col. Dorr divided his command, placing the three battalions approximately thirty

miles apart along the railway. He broke up the First Kansas Battery among the

battalions, two guns to each, for additional firepower. E.B.

Doane’s 2nd battalion was stationed thirty miles west of Nashville. Most

attention, however, was centered on Waverly, where Col. Dorr established his

headquarters.

One cavalryman wrote home:

Our battalion (the 1st) have invited themselves to spend some time,

perhaps the winter, with the good people of this place. If our sensibilities had

not been blunted by soldiering we might have thought we were not very welcome

guests, for our reception was not very cordial. They used very abusive epithet

to the men; said we had just come to plunder them and destroy their property,

and that their gallant defenders would not permit us to hold the town many days.

By the way, the only manifestation of the presence of the aforesaid “gallant

defenders” we have had is when under the cover of darkness they have concealed

themselves and fired on our pickets, but we wouldn’t take the hint, and

we stayed.

This is the county seat of Humphies County, and at the commencement of the war

was in flourishing condition, but like every other Southern town, is reaping the

fruit of secession... There has never been any Union troops here before, and the

inhabitants have very appropriately named it the “Rebel Heaven”. Here they have

met and organized their plundering expeditions with perfect safety, for there

were no Federal troops closer than Fort Donelson, and when forced to retreat

from other parts of the State, have come here for protection... Almost daily

Col. Dorr has companies out scouring the country in all direction. The good

results of this system are already manifesting themselves. Every day the town is

crowded with citizens. Nothing more is required of those who have never aided

the rebellion than taking the oath, but the others are placed under heavy bond,

and as they all have property in this immediate vicinity, their bonds can be

depended upon.

Because of the constant patrolling and the large number of guerrilla

forces, it was not long before E.B. Doane saw combat. His commander, Captain

Root, described a “picket fight we had on the 7th in”.

It having been ascertained by an intelligent contraband that came into camp

about 5 o’clock on the 7th, that there was a band of guerrillas

hovering around our camp, it being too late in the day to send a force (sic) out

after them, Maj. Thompson in command, concluded to strengthen the outposts and

keep a sharp lookout for them. Orders were given for every man to sleep on his

arms, to be ready in case of attack. Sure enough just about eleven o’clock Post

No. 1 and No. 2 were attacked by a superior force. It being dark it was very

hard to tell their number. Receiving orders to ascertain the strength of the

enemy if possible, I rode to Post No. 2 ,as the fighting appeared to be the

heaviest at that Post. It soon became apparent that their intention was to

destroy the railroad. Having ordered 25 men to dismount, they were thrown

forward, when a general fight ensued for two or three hours. The rebels having

superior numbers drove us across the railroad. Then with a dash we would drive

them back, keeping the road clear. It being too hot for them after trying at

three different points to destroy the tracks and failing to do so, they beat a

hasty retreat, carrying off their wounded, leaving their dead on the field.

Casualties on our side, Lt. E.B. Doane, flesh wound in the face, slight...Lt.

Doane was the officer of the guard or picket, and was at Post No. 2, where the

fighting commenced and it was through his daring and bravery that the Post was

held until reinforced...

E.B. Doane wrote to the Keokuk editor:

Mr. J.B. Howell,

If agreeable with you, I propose through your columns to inform the home friends

of Co. E, of a little Christmas scout we have been having after some of our

guerilla friends. We were out five days, subsisting both men and horses off the

wealthy secesh farmers pointed out to us by our guide, and we fared well too.

Our scout was in the direction of the Tennessee river, principally on the waters

of the Piny and Duck rivers. We had one engagement resulting in the rout of the

noted Col. Hawkins and staff, the capture of four Captains and nine men, one man

killed and another (like the swine of which we read,)

ran down into the river and drowned. The enemy brought on the engagement by

firing from ambuscade a volley into the front of our columns, shooting Captain

Root through the hat, which they supposed would check our advance until by a

running fight and the speed of their horses they could escape. But they found to

their sorrow that it took more than a volley of revolver shot to check Captain

Root and his column. I can hardly believe a volley of grape and canister would

have done it. For every one charged directly upon them, yelling like so many

demons. Those guerrillas are choice men, mounted on number one horses and armed

to the teeth. Their business is to plunder and abuse Union citizens and harass

our advance by dashes and daring raids, and destroying bridges, railroads and

supply trains. And it is only by constant and rapid scouting that they can be

kept out.

For a week past we have been visited with snow and cold weather. But prior to

that it had been remarkably warm and rainy. The health of the Company is good,

and the entire Regiment seems to be blest in this particular. Deserters are

coming in almost daily. The late Proclamation of Amnesty by the President will

take half the men out of the rebel ranks, especially near the front. We have

reliable information that the enemy can no longer depend on a picket, which is

certainly a bold indication that they are fast playing out. As fast as the main

line is moved to the front the railroad is being pushed forward too, principally

by black labor. Thus, instead of “Sambo” supporting the rebel army, he is

helping get it forward to us.

Respectfully,

E.B.D.

One Kansan stationed with E.B. Doane’s battalion described the miserable

weather:

The winter of 1863-’64 was noted as a cold one, breaking all records. The little

creek known as Sullivans Branch, twenty-six miles from Nashville, upon which we

camped, was frozen almost solid. At this camp, although in daily communication

by rail with the great depots of supplies at Nashville, we suffered the greatest

hardship experienced during our entire army life, because of the villainous

character of the rations furnished us. These rations consisted solely of salt

pork—the lean streaks between the solid fat portions having in many instances

turned green-hard-tack, sugar and coffee. In consequences of this meager diet I

acquired a severe attack of scurvy...

In such scattered fights, the 8th Iowa captured over five hundred

guerrillas.

But it was difficult and tedious warfare.

The winter was severe and supplies were scarce, and there was no decisive

fighting because each army was preparing for the renewal of offensive operations

in the spring.

Men were tired and lonesome. E.B. Doane wrote:

Dearest Amelia:

(For to me you are certainly the Dearest on earth). Your very acceptable

letter was received today and it did more good than anything I have seen or read

since I have been out. It found way to hidden affection, that I knew not of and

if I loved you before, I cherish and almost adore you now as the hope of

my coming happiness.

The prayer and affection of a Christian Lady to the mind, affection and

character of a lonely Soldier is like the soft distilling dew or a gentle shower

of rain to the drooping bud. With regard to my affectionate heart perhaps I

would have had an affectionate one if those finer feelings had been cultivated

as they should have been when I was younger. But I feel that they were blighted

in the loss of a tender mother when I was quite young, hence with no one to

nourish and cherish those finer senses they remained a mere-------until I was

old and large enough to begin to think about loving some one as partner for

life. And now I feel (as doubtless you have noticed ere this) that I greatly

need those feelings nourished and cherished by some faithful and affectionate

friend. Yet as far as my feelings of affection extend, you shall enjoy with

pleasure to me. I received a letter from a certain young lady

who stated that she was at the festival at Sharon Church and saw my old lover

there. I also had a letter from Mr. Maris hinting as though he wanted to know

something. My Health is better. Health is generally good and the weathers fine.

Farmers are ploughing. This State holds an election next week to reorganize the

State Government. The Army at the Front is advancing and I expect we’ll go there

soon. Wish I had been home as you heard. I will come if (I) can. But don’t look

until you see me coming. That is a nice rose. I’ll keep it as a token of love

from a Dear one. I said I was better, but I am Love sick and I expect

that will make me homesick. I really feel that I am blest in having such

a Friend as you to write me such good kind letters. I am

glad they held the Meeting and had the dinner at the Church. If a Meeting

indicative of Friendship and regard for the Soldiers who

are fighting not only for the preservation of our Government but

in defense of Religious liberty and the right of a free

people to Govern themselves is not worthy of a place in the

Altar even of Paradise, then we had better sheath the Sword and prepare

for an Eternal abode in Despair. If there is anything I

detest it is a base Copperhead that’s too mean to protect

the country that has protected him and really made him what he

is and gives him the positions he now holds and too

cowardly to go and fight for what he advocates. Oh, But there

is a time coming when such men will wish to God this had been a

blank in their lives. I have more respect for the Enemy who meets me

in deadly conflict than one of those white livered fellows. But

I’ve said too much on this, yet I feel it and if I had my way they would have to

leave the country for want of associates.

When I come home we’ll have a nice horseback ride. Your little Horse looks fine.

I don’t ride him much. It’s too nice to kill up in this country. I shall have to

close. Its time for dress parade, with many warm wishes for your comfort and

enjoyment and hoping to hear from you... I remain your true and sincere friend.

E.B.Doane

Unknown to him, his brother Ithamar had died just the day before. Ithamar, a

year younger than Eleazar, had remained in the 19th Iowa Infantry,

which had taken part in the siege at Vicksburg, and then gone on to New Orleans.

Sometime that summer he fell ill, and on September 8, 1863, he wrote home that

he was in the regimental hospital: “I am quite weak but able to walk about the

house some and sit up about half the day. I have had the Diareah nearly all the

time since I came down the River and then I took the Fever. It has been the

hardest spell I ever had...There is still a good deal of sickness here.” Several

months later, the entire time spent languishing in the hospital, he was

furloughed home. The trip was too exhausting, however, and he died in Salem,

Iowa, February 25, 1864, one week after his return. The medical report listed

cause of death as chronic diarrhea. Eleazar would learn of Ithamar’s fate within

a few weeks. The news could only have increased his hatred of the South’s

rebellion.

However passionately one may grieve, one cannot exist on hatred, and the Iowa

cavalrymen were kept busy to prevent their brooding on death. What did the

troops of the 8th Iowa do? The same as in any army: real and

artificial business (drills, scouting, guard duty), reading papers, writing

letters, and talking. Politics was an impassioned subject. Captain Root wrote

home:

I see by the papers that the Presidential campaign has fairly commenced-all the

soldiers ask for is for the Union party at home to stand by OLD ABE, as we think

he is the man, and the only man to place in the Presidential chair at this

critical time. But let it be Lincoln or any other man, all we want is a man that

will carry out the present policy of the government, and woe be to that man or

party that dare say peace till the proud flag of our country floats over every

rebel strong-hold, and those miserable traitors that have been the means of all

this unholy war suffer to the fullest extent for their crimes.

His attitude was undoubtedly shared by E.B. Doane.

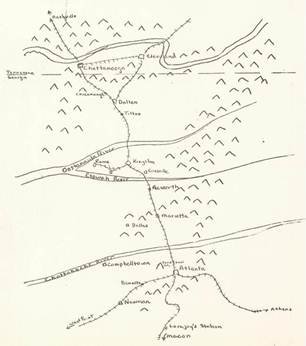

Early in March General Grant was promoted to command all the armies of the North

and left for the east. General William Tecumseh Sherman assumed command of the

Army of the West with orders to press on to Atlanta against Johnston’s

Confederate forces. To relieve the overworked supply system, the Union forces

stripped themselves of all but the most necessary gear and reassembled at

Chattanooga and Cleveland prepared to press south along the rail lines toward

the Confederate position at Dalton. E.B. Doane’s unit rode to Nashville on March

14 and was assigned to McCook’s First Cavalry Division. The duties of the

cavalry were to provide a screen along the front and flanks of the advance and

to disrupt the enemy position as much as possible. Over one-hundred thousand men

began to move south.

E.B. Doane saw this as an opportunity for advancement. On April 5th he had been

promoted to Captain of Co. E.

He wrote to his fiancée:

Dearest Amelia,

Tonight I was favored with your highly

prized Epistle of the 30th. I was truly glad to hear from you, for I think of

you often, quite anxiously too. I wish I could interest you better, but I am

tired and in a hurry, and can’t write much this time. We have been on the March

ten days and will go on to Cleveland 30 miles east of here. We are camped at the

foot of Missionary Ridge over which the Battle was fought. Today we crossed the

front of Lookout Mountain. We have been rained on every day since we left

Nashville and have had a very rough road. The road across the Cumberland

Mountains was so hard that we walked and led our horses and then walked back and

carried our things that were in the wagons. Three of our wagons were broken to

pieces crossing. There are a number of troops coming to the front now and I

expect something is to be done soon. The enemy is in line about 20 miles from

here. But if they couldn’t hold the position they had here, I don’t think they

can any other. I send you Lt. Anderson’s photograph. He is 2nd Lt. of

our Co. and I’ll send one of Capt. Root’s if I can get it. Give mother & father

my respects & to the rest of the family too, and tell Mary Jane I’ll bring her a

Bear again on the 4th of July. I guess I’ll hardly forget that Exhibition or

that night or the one I was with soon either.

I’m sure your letters are not lacking in interest. I’m glad you are enjoying

yourself so well. I hope the time not far distant when I can see you again,

Dear. I am well. Capt. Welder has returned. Please write soon and accept the

warmest wishes of your Friend and Lover,

E. B. Doane

There had been some illness and some dissension among the officers regarding

discipline, which resulted in the resignation of several officers of the Eighth

Iowa,

but neither the efficiency not the morale of the unit was seriously affected.

One cavalryman wrote home:

We had quite a gay time on the road from Nashville. The roads were very bad, and

would have been considered impassible for anything but a Government train, which

may go through, though at the sacrifice of the lives of many animals. I don’t

think I would be exaggerating to say that I saw the bodies of two thousand dead

horses and mules on the road.

From May 7, 1864,

the day Sherman began his offensive into Georgia, to July 30th, the 8th

Iowa was in continual combat.

On May 9th Col Dorr led Company E up a steep, open field to determine where the

enemy lay; only the Confederates firing high saved the unit from heavy

casualties; every day thereafter the Iowa men were involved in a running fight

with Confederate cavalry while screening Sherman’s march across some difficult

mountain terrain toward Dalton. This outflanking maneuver forced the

Confederates to pull back across the Oostanaula River. Sherman then outflanked

the defensive positions there as well. As Sherman pressed south through the

mountainous and unmarked country into the relatively open land north of the

Etowah, he scattered his troops along several lines of advance, looking for

Confederate weak points. Although this seemed risky, tempting his opponent to

stage an ambush or counter-offensive, Sherman could rely on his experienced

commanders to exercise a combination of boldness and caution which had appeared

only rarely earlier in the war. By now the Union officers were proficient in

their performance of duty; moreover, unlike many officers in the Army of the

Potomac, they were accustomed to victory and, therefore, confident in their

ability to carry out the most difficult and hazardous of assignments. Sherman

was seeking a fight. The opposing commander, General Johnston, in contrast, was

determined to avoid any engagement which did not promise a major victory at

relative low risk. He could not afford to have his army worn down by repeated

battles, as Lee was

experiencing

against Grant; he had to preserve his troops for that moment when Sherman made a

mistake, or until Sherman’s supply lines became so long that most of his troops

were tied down protecting them. Nevertheless, he knew that his army’s morale was

suffering from the repeated retreats. At Cassville, tempted by Sherman’s

provocative and aggressive advances, Johnston sought to destroy one wing of the

Union army by concentrating his entire force against it. No decisive battle took

place, but there was a spirited engagement with Union cavalry. The 8th

Iowa and Major Root were cited for distinguished conduct in their charge upon

the Confederate flank. The next day Johnston withdrew further south and the

Union troops occupied the abandoned trenches.

experiencing

against Grant; he had to preserve his troops for that moment when Sherman made a

mistake, or until Sherman’s supply lines became so long that most of his troops

were tied down protecting them. Nevertheless, he knew that his army’s morale was

suffering from the repeated retreats. At Cassville, tempted by Sherman’s

provocative and aggressive advances, Johnston sought to destroy one wing of the

Union army by concentrating his entire force against it. No decisive battle took

place, but there was a spirited engagement with Union cavalry. The 8th

Iowa and Major Root were cited for distinguished conduct in their charge upon

the Confederate flank. The next day Johnston withdrew further south and the

Union troops occupied the abandoned trenches.

By now the respective strategies of the two commanders was clear. Sherman wanted

a battle in the open so as to destroy the Confederate army. But he would not

assault prepared positions. That would be an unimaginative use of his

superiority in manpower, probably too costly, and most likely ineffective.

Instead, whenever he encountered trenches, he would have some troops dig in

opposite, so that the Confederates would have to be ready to meet a direct

assault; with the rest of his army he would move laterally, outflank the fixed

positions and force the enemy to choose between a pitched battle on open land or

retreat. Johnston, on the other hand, had too few troops to fight that kind of

battle. Each time he was faced with such a choice, he retreated, hoping the

extended northern supply lines would require more garrison troops and reduce

ever more the actual combat forces opposed to him. Meanwhile, he was gathering

reinforcements; although he soon had almost as many men as Sherman, his North

Georgia militiamen were relatively untrained, often pro-Union, and prone to

desertion. At every strong point Johnston prepared elaborate defenses, such as

could bleed Sherman’s forces to death if he attacked head-on. From Cassville

Johnson fell back to Marietta, where he prepared to make another stand along the

railroad line.

On May 22nd Sherman began to outflanked the Marietta trenches by moving overland

toward Dallas, with each man carrying his own rations and equipment; he sent the

cavalry ahead, McCook’s division (and the 8th Iowa) in the lead. Two

days later E. B. Doane’s unit charged and routed a superior force at Burnt

Hickory. The following day, May 25th, there was a sharp combat at New Hope

Church near Dallas. There Lt. Anderson took a rebel battery and held it several

hours against desperate counterattacks before being ordered to withdraw.

Both armies then entrenched themselves. These defensive works were constructed

on these principles:

The

general...determined the most available line for defense, and directed brigade

commanders to form their troops upon it, following the outline of the ground and

making such angles, salient or re-entrant as it required. The

skirmish line was kept in front, the rest stacked arms a few paces in rear of

the intended place for the breastwork, entrenching tools were taken from the

wagons that accompanied the ammunition train, and each company was ordered to

cover its own front. Trees were felled and trimmed, and the logs, often two feet

thick, rolled into line. The timber revetment was usually four feet high, and

the earth thrown from the ditch in front varied in thickness according to the

exposure.

The Eighth Iowa

held a line one and one-half miles in length until July 1.

But E. B. Doane was not present when the army moved south again. The cause of

most fatalities in the war was not battle, but disease. Epidemics ran through

entire armies and hospital facilities was completely inadequate. On June 20th E.

B. Doane was overcome by illness. He relinquished his command, but remained with

his company until ordered to the hospital by the surgeon. He was taken to

Ackworth, Georgia, and three or four days later was evacuated along the railroad

to an Officers Hospital in Nashville.

Miss Amelia:

Dearest Friend. Today I feel better and more like writing you. But I can’t write

a good letter yet. I’ve been improving considerably. Yesterday I rode (in a

carriage) down town, but it was a big job. The weather is quite warm. I wish I

could get a leave of absence a few days when I get stronger. Which I may do. But

I think it uncertain. But it won’t be my fault if I don’t. I’ve had no mail

since I came here. I shall look anxiously for a letter from you in few days. I

expect there’s some at the Regt. I have sent for it. But it may be sometime

before it come and it may not come at all.

We still have encouraging news from the front. I’m so sorry that I’m sick now

when there is such a good chance to distinguish ones self and gain a better

position. If I could have had good health and come through this campaign safe I

would have made a Field Officer easily. You need not be surprised if I get it

anyway. I’ve worked hard for it and ran a great many narrow risks. I know I’ve

earned it well. And if they don’t promote me to it soon, I guess I’ll come home

to my Amelia Dear!! Will that be right? There are wounded and sick coming

in every day from the front. Several of my co. are in the Hospital back about

town wounded and some severely, too. But I’ve been unable to go and see them

yet. I think I shall try it soon though.

I learn that Mrs. Spurries, an old Schoolmate of mine and classmate too (at Mr.

Howes) is teaching at Primrose. Have you become acquainted with her yet? She was

(portion damaged) to a soldier home on Recruiting Service. He too is a

schoolmate of mine. He is in the 14th Infty. I still get a letter from Mr. Maris

occasionally. He likes to talk Patriotism better that act it, I

think. How do you enjoy your school? Are you going to have a fine celebration on

the 4th? The Potomac Army is to celebrate the 4th in Richmond and the Georgia

Army in Atlanta. I wish I could help do it. And the next 4th with (portion

damaged). Won’t that be nice? Please write soon. Direct to Capt. E. B. Doane,

Officers Hospital, Nashville, Tenn., leaving off the Co. and Regt. or else it

will go on to the Regt. With many warm wishes for your enjoyment and well being

I bid you Good Bye.

Your Affectionate Friend

E. B. Doane

A month later he was still in Nashville, but he was much healthier. He wrote

home:

Dear Brother and Sister,

Today I received your welcome and interesting letter of the 10th & 13th

Inst. I was truly pleased to hear from you and to know that you were well. I

would indeed like to come home for awhile and if I had known that I would not

have been able for duty before this I should have come. But now I shall go to

the Front soon, in about a week I think. I am not well, but I won’t live here. I

am better though, and think by taking good care of myself I’ll get along.

Governor Stone was here today and will go to the Front soon.

Perhaps I’ll go down with him. I’m glad that money got through safe. I sent 100

dollars more. It was a check on New York Bank. I sent it in a letter. Please

write as soon as you get it for I’m uneasy about it. If it’s lost I can get

another one here before I leave. When you write again tell me how much corn and

so forth you had and whether all the farm was cultivated or not. I’ve only had

one or two letters from you yet. I expect that others are at the Regt. Capt.

Hoxie of the 8th was married here today. His Lady came from Vermont.

I was at the wedding. I had a letter from Franklin today. He is well and at

Kingston, Ga. and says my horses are doing well. Is your school a good one and

what do you study? Try and go all you can and every day this winter. Please

write soon and often direct as before until I write to change it. Tell Father to

write soon. Give my respects to all.

Meanwhile, Sherman had moved past the strong Confederate positions at Marietta

and Kenesaw Mountain, forcing Johnston to withdraw across the Chattahoochee

River. The 8th Iowa was the first cavalry unit to cross the river in

pursuit.

Sherman planned to continue his advance south by outflanking the carefully

prepared entrenchments, just as he had done before. This time, however, he faced

a new enemy commander, John Bell Hood. The Confederate high command, believing

that Johnston’s tactics were too cautious, replaced him with a true fighting

general. Hood, who had lost at arm at Gettysburg and a leg at Chickamauga, was

an impulsive gambler. He quickly launched a series of desperate attacks against

the Union line. The 8th Iowa position was assaulted on July 23rd

and 27th, about the time E. B. Doane returned.

Hood’s costly attacks so weakened his army that the Confederation high command

reinstated Johnston in command. Sherman quickly resumed his flanking movements,

forcing Johnston to commit so many troops to permanent defenses that he would

either spread too thin to hold the center or would have to fight to avoid being

surrounded. He hen ordered General McCook to make a deep raid into Johnston’s

rear, disrupting communications and drawing troops away from Atlanta.

One member of Company E described the raid:

Our regiment numbering tow hundred and

ninety men, (the remainder being dismounted and in camp at Kingston, Ga.), in

company with the remainder of our division, started on the 27th

ultimo to make a raid through central Georgia.

We crossed the Chattahoochee River to

the west side and moved down about twenty miles, to Cameltown. We recrossed the

river on the morning of the 28th and struck the Atlanta and West

Point Railroad, at Palmetto Station—We destroyed several miles of the road at

this place, after which we pushed forward with great rapidity toward the Atlanta

and Macon road, which we reached on the morning of the 29th;

destroying while en route, over eight hundred wagons loaded with Government

Stores—The mules were sabered, as we were unable to take them with the command.

On arriving at McDonald’s Station on the

railroad, Major Root was ordered out with a portion of the 8th Iowa,

and succeeded in capturing and burning a train loaded with Tobacco, Lard and

Arms.—The tobacco alone was estimated at one hundred and twenty thousand

dollars.—After effectually destroying several miles of the road, the command

proceeded to return.

When but a short distance from the road

our column was attacked by a heavy force of rebel cavalry, and the 1st brigade

was entirely cut off. Major Root was ordered to take the 8th Iowa and

charge to open communications.

The men charged with revolvers, and a

desperate hand to hand fight ensued, but they were finally driven back.

Twice they charged, and twice were they

pushed back, by an overwhelming force. The Major’s horse was killed in the first

charge, and he received a severe injury in his right shoulder, nevertheless he

was not found wanting when the second charge was to be made.

General McCook came up with the 2nd

brigade, and succeeded in cutting thro’ and the command moved rapidly toward the

river, and reached Newman’s Station on the morning of the 30th. Here the 4th

Ky. was attacked and two companies were captured. We soon found that the enemy

had a heavy force in our front and on our flanks. The division was halted and

the forces so disposed as to deceive the enemy. Our regiment was ordered as

skirmishers and to discover the position and strength of the enemy; we found the

enemy endeavoring to surround our force; his line at that time running in the

shape of a horse-shoe, the opening being toward the south, and that their forces

consisted of cavalry and two brigades of infantry. The engagement soon became

general along our whole line; the enemy making repeated charges, and were as

often repulsed.

Major Root was then ordered to mount his

command, and charge down the road leading to the river. He moved his command

back and advanced cautiously down the road until within sight of the enemy, and

then ordered a charge. The boys soon found themselves confronted by Ross’s

brigade of Texas Rangers; but nothing daunted, they dashed into their lines and

drove them back, compelling then to abandon their horses, as they were

dismounted at the time, and captured over five hundred horses, and finally

succeeded in clearing the road; but they were closely pressed by superior