O. C. Bell, Coach

between the Old Football and the New

By

William Urban

The years 1905-1906 were marked by intense discussions—hardly a college

faculty or high school board was not divided by accusations that the sport had

grown too brutal and retorts that manliness was under yet another attack. The

sport was coached by professionals only at the largest universities, with small

colleges and high schools still making do with volunteer faculty, some of whom

were more acquainted with the ever-popular game of baseball and newly-introduced

basketball. At Monmouth College this changed during the two years that Oscar

Clifford Bell was athletic director.

When

Bell was born in Biggsville, Illinois, March 15, 1880, there were few rules for

football other than not to gouge out an opponent’s eyes while he was trapped in

a rugby-style pile, and throwing a ball forward was worthy of a referee’s stern

reprimand. Over the years agreements were reached on how to mark a field, on

limiting slugging, lessening interlocked blocking and low tackling, and use of

the flying wedge. As the years

passed, football heroes made the sport more popular, until almost every high

school and college was fielding a team. As participation grew, so too did

concerns over the safety of the players.

Outraged competitors attributed this to the two star trackmen being 23 and 24

years of age, a charge that census records prove false.

Cliff Bell entered the

After earning his Bachelor of Laws degree in 1903, he became

principal of the

His track team lost the first

meet to

Happily, the Ravelings of the

next years contained detailed descriptions of each sport and often each athlete,[8]

and the local paper, the Monmouth Review,

covered each game in detail. 1905 was also a good year for Monmouth College,

which had a new high in enrollment;[9]

and for the community—the interurban to Galesburg and to Moline were almost

finished,[10]

construction was about to start on the Colonial Hotel, and the first

Kindergarten was being organized.

It was, however, not a good year for football. Critics pointed to the

rising toll of players who died or were injured, with teams deliberately maiming

opponents’ key players and adding non-students to their own rosters. Such

criticism had been growing for years, but it had no focus until President

Roosevelt’s son announced that he would play football at Harvard. TR immediately

realized that Kermit would be singled out for rough treatment unless something

was done. Not a man to stand back when it came to taking a stand, TR immediately

called the presidents of Harvard, Yale and Princeton to the White House; soon

afterward the American Football Rules Committee was established, leading to the

sports association that evolved into the NCAA. It was not that TR was a sissy—a

college boxer, western rancher, New York Police Commissioner, and head of the

Rough Riders in the Spanish war, he believed in the strenuous life, but

football, like politics, had to be made safe for gentlemen.[11]

This

would have its impact on all Illinois colleges and high schools, but especially

so on Monmouth College, which was proud of its football history—though the

rivalry with Knox College was scarcely appreciated at the time, the series of

games that started in 1891 (actually 1888, but there was no team fielded in the

two years to follow) would become the oldest rivalry west of the Appalachians.

Football was evolving rapidly, led by the large university programs, but

followed enthusiastically by a multitude of small schools that had not yet

realized the need for extensive recruiting, training, and publicity.[12]

Certainly small colleges could not recruit players beyond the personal contacts

of the coaches, the alumni of the college, and the enthusiastic support of local

newspapers; facilities were primitive, but stretched each college’s limited

budget significantly; and a significant percentage of faculty and clergymen in

the denomination believed that the sport was dangerous, wasteful and teaching

impressionable young men all the wrong lessons.

Even

scheduling games was far from a science. Teams promised to appear, then begged

off. Students promised to play, then did not show up. Athletic facilities varied

in quality—usually from bad to worse. The

Monmouth College Catalog warned, “There shall be no match game played on the

Park or any ground whatsoever during recitation hours, without consent of the

faculty,” and “We seek not to make athletics so prominent as to interfere with

mental work, but to direct this necessary adjunct of college life that it give

recreation and vigor of body and mind to the student.”

And

that was the heart of the matter! Was Christianity the realm of the mild and

gentle Jesus or the vigorous religion of Theodore Roosevelt? Was a

denominational school to turn out “namby-pambies” or models of manliness that

would attract youthful males into the churches and colleges?

If

the intent of the Monmouth administration—just recovering from the financial

crisis of 1898-1901—was to minimize the enthusiasm of the students for sports,

it was no more successful than the strenuous efforts to eliminate consumption of

alcohol, smoking and playing cards. It was, after all, one of Monmouth’s most

revered professors who adapted this favorite song from the popular

Bingo repertoire:

Here’s to

With

her wisdom and her knowledge.

Drink her down, Drink her down.

Drink her down, down, down.

Still, admission standards were stiff—at least one year of Latin, Algebra,

Geometry, English, History, Geography, Physics and Biology. That explains why

266 students were in the Music Conservatory and the Choral Society rather than

in the preparatory and collegiate divisions. Inevitably the 94 freshmen would

dwindle down to 32 seniors—and juniors and seniors made the best varsity

material. For the Conservatory only a belief in one’s musical talents was

required—the Music faculty was very good at turning out splendid choir groups,

quartets and individual performers, but not running backs. The college buildings

were few in number—Old

There was more interest in the annual Pole Scrap between the freshman and

sophomore classes than in intercollegiate athletics.[14]

Students participated in debates, plays and concerts; and the spring celebration

in Valley Beautiful with the May Pole, dancing, singing, and faculty acting in

farces, was a

Although small groups of non-athletics followed the football games closely,

school spirit was not high—there were complaints about apathy aplenty, plaints

best expressed in The Football Player’s

Soliloquy: “When all is said and done, did it pay? What has been gained by

it in any way? Wasn’t the old fellow right, who came around with his long pious

face declaring us all little better than brutes and wondering what the world was

coming too (sic), that a christian college would allow such a return to

barbarism?”[15]

Several pages later he became a philosopher: “What of the joys of victory and

the sorrows of defeat? Well, it’s sort of fine to be a hero in the winning game,

but there is a lot more strength in being able to take defeat like a man.”

Although

The warm-up football games in 1905 against high school teams were counted

in the season record—with good reason in an era when boys went to high school

into their twenties (remember the complaints about Bell being 23) and were

toughened by hard physical labor on farms and in factories.[19]

In most sports high school teams held their own against college men. The college

usually made up for this by audaciously scheduling university squads—in 1903

Monmouth lost to the University of Chicago 0-108,[20]

in 1907 to Missouri 12-6; eventually ended the long series with Northwestern at

5-7.

Next

week’s 40-0 loss to

The

next week he made a special visit to

The

dull, cold day sends through my bones a dread of tables turned.

Let

we should lose the championship, now so nearly earned.

Through the season we have come, nor suffered one defeat.

The

roaring bleachers now affirm, today we will not be beat.

And

I will play; aye, play!

Must, on me depends the game.

Well

I know that every man regards it just the same.

What

bumps and breaks await me there,

Now

gives me no concern,

One

thing alone I know or care;

‘tis

“Honest Victory Earned!”

I’ve

played it all while waiting here, and now must play again.

For

there sounds loud the call of

The

last practice was a “Forty Minute Grind,” but it paid off in a 23-0 victory over

Immediately

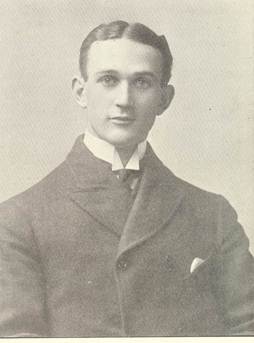

The Ravelings summed up the

year with a spoof of faculty minutes that reported, “Prof. Bell called attention

of the faculty to the fact that he is making good. Reports that the student body

has not yet gotten next to the fact that he is planning for essential complete

control of Monmouth athletics.” His photo shows a handsome, thin man in an

elegant suit.[27]

By the end of the season it was clear that football would be different in

1906. The reforms had been announced—stronger rules against roughness, no more

“hurdling” (throwing a small player over the scrimmage line holding the ball),

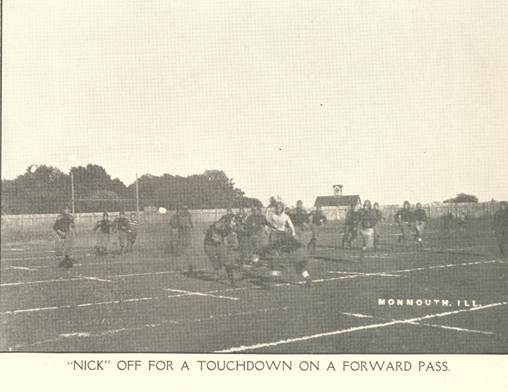

better pads, legalizing the forward pass (but under restrictions that included,

in the case of an incomplete pass, giving the ball to the other team), requiring

teams to make ten yards instead of five to get a first down (in three plays

instead of four) and ending the practice whereby a punt was a free ball for

anyone who could land on it or wrestle it away from an opponent.[28]

The game was also shortened from seventy minutes to sixty, with the ten minutes

allotted to a half-time break. Still, if the referees were any good—a doubtful

prospect—the game would be less violent. More significantly, the game boded to

become too sophisticated for a student or volunteer faculty manager. The

professional coach appeared—a man who would command, not cajole. Cliff Bell was

a prototype.

But 1906 was not an easy fall for O.C. Bell. His father had died in June,

then his sister Olive dropped out of the Conservatory to marry and move to

In

spite of the enthusiasm of the students and the high hopes expressed in the

Monmouth Review of Sept 6th,

the “Bell Machine” almost didn’t appear. In fact, the season was one long series

of crises, beginning with his inability to meet the new students because he was

involved in the registration process. Then several key lettermen began skipping

practice—one had a sprained wrist, another had already played “four or five

years” and was tired of the sport, a couple needed to study, and one was the

lead orator in the debate contests.[30]

After attendance had fallen so low that Bell could barely field two squads, he

invited the local high school to scrimmage in practices; then on September 18th

he warned the student body after chapel that unless the players came to

practice, he would cancel the next game—the vote to continue the sport was

unanimous, and the students ended the session with spirit-raising yells. Few,

however, took up his offer to let them try out for the team.

The next bad news was from the universities he had hoped to play—

The first game—October 1st,

was only a thirty minute contest against

A week later most of the missing

players were back. The game with

Desperate to find an opponent,

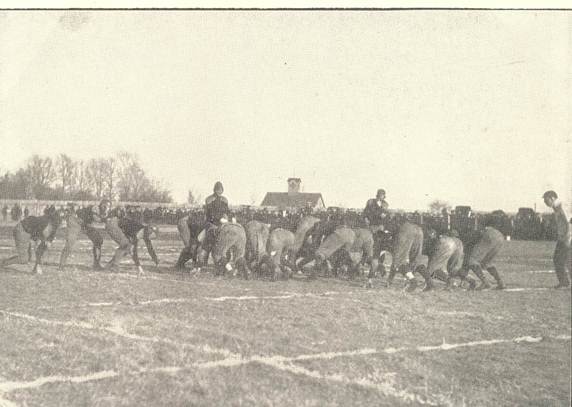

The Millikin fans were much

better. 200 Monmouth students took the train to the contest. Billed as a

“championship game” of undefeated teams, it was “not a walkaway.” Downright

miserable, in fact. There was a “cold raw northwest wind blowing down the field

that chilled both players and spectators.” Nevertheless, “the game was played in

Monmouth’s usual whirlwind style, little time being taken out.”[35]

Monmouth students joked that the opposition should have been named “Mili-kan’t.”

That was unfair—Millikin had scored in the closing minutes, but 25-9 was a

decisive win.[36]

Awkwardly, Illinois Wesleyan

cancelled the next game, saying that its team was too crippled to play. But

obviously the word had gotten around.

The upcoming

At the end of November there was

a “Battle Royal” on the field down Broadway—the game against the champion of

It was a short season, only eight

games (counting the two high school contests), but only Millikin had managed to

scare against

No doubt that

The new football rules were universally popular. The number of fatalities

declined, markedly in college ball. The

Little is known about

The community was stunned

He was as good as his word. Bell is pictured with the 1906-07 basketball

team that won its first six games before losing two in the final seconds, then

defeated Macomb Normal (now Western Illinois University) 46-12.[45]

There was a farewell party on February 28th. After several

speeches praising his coaching skills, the students presented him with a gold

signet ring, saying that they hoped he would “accept it and keep in as a

reminder of his Monmouth associations.” He “received the token of

friendship—very gracefully.” Then, “in a few well-chosen words, he re-called the

many pleasures that had been his during his terms as coach of the institution.”

He credited his success to the support of students and faculty, and that of

people who wished to advance the interests of the college. He urged everyone to

support his successor. The whole ceremony was one that, in the opinion of the

Review, “will long be remembered by

Coach Bell.”

That morning A.G. Reid had arrived by train, in time to attend chapel. It

is not known whether or not he met

In sum, in his two years at

Monmouth “O.C.”

His specialty was track, and he coached baseball as well. The 1908

Ravelings commented that “no one in

the history of the college has put forth more effort, been attended by more

success, or raised athletics to a higher standard.” His method was that “he

exercised rigid discipline and got more from his men than they thought

possible.”

Roosevelt approved of the changes: “It is to my mind simple nonsense, a

mere confession of weakness, to desire to abolish a game because tendencies show

themselves, or practices grow up, which prove that the game ought to be

reformed…. But there is no

justification for stopping a thoroughly manly sport because it is sometimes

abused….”[49]

The census of 1920 found him in

Shortly afterward he became chief examiner of the Cleveland City Civil Service

Commission, then chief police prosecutor of the Municipal Court. In 1923 he was

elected Municipal Court judge, a position he held for the rest of his life.[53]

He was active in civic affairs—a

member of the Cleveland Bar Association, the Big Ten Club, the City Club and the

Fraternal Order of Eagles. The Census of 1930[54]

found him a municipal judge in

With proposed football reforms once again in the news, maybe it is time

to remember. Meanwhile, there were multiple turning points in the past of any

sports history, some—like major universities’ teams—well researched; others—like

those of small colleges—virtually unknown. Indeed, many of the small colleges of

that day are now defunct, their demise partly due to the fact that they could

not attract male students, perhaps because they could not afford programs that

would attract male students. And one rule of thumb here (or ring finger) is that

“no boys, no girls.” Similarly, in an era without dormitories, cafeterias, and

student unions, students needed multiple events on campus to fend off boredom.

Visiting lectures, debates, musical programs and YMCA events were enjoyable, but

hardly exciting. Sports provided that outlet for youthful energies and the drama

that daily life so obviously lacked.

The history of the small programs, more so perhaps than even that of the

larger programs, is the story of individuals who worked with limited means to

produce winning teams. Bell, for instance, traveled almost exclusively by

train—thus, it was impossible to visit many high schools and speak to players;

in an era when sectarian identification was important, Monmouth being

Presbyterian was a mixed blessing—the historical denomination was comparatively

large, but Monmouth was Associate Presbyterian, a relatively small body which

divided its young people between six colleges. Community support was strong, but

more people followed high school football than the local college team.

Lastly, there was the expense.

Monmouth could not afford to meet the salary offered by a second-tier

university. In fact, the very survival of the college was sufficiently in doubt

that the fire which destroyed Old Main in 1907 came so close on the heels of the

financial crisis of 1898-1903 that one might credit the successful football

program for making the denomination’s churches, the alumni, the townsfolk, and

potential students in nearby communities aware of the college’s claim to be a

worthy educational institution.

Of course, one could make the

same claim for the Music Conservatory—and for the same reasons. No one person,

no one activity was decisive. But no high profile activity—as football certainly

was—can be ignored.

An edited version of this was printed in

Monmouth, the Monmouth College Magazine,

26/1 (Winter 2011), 28-29.

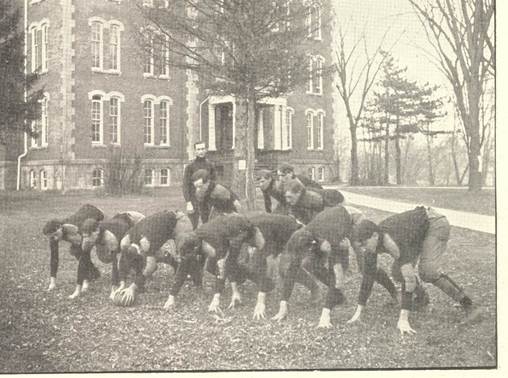

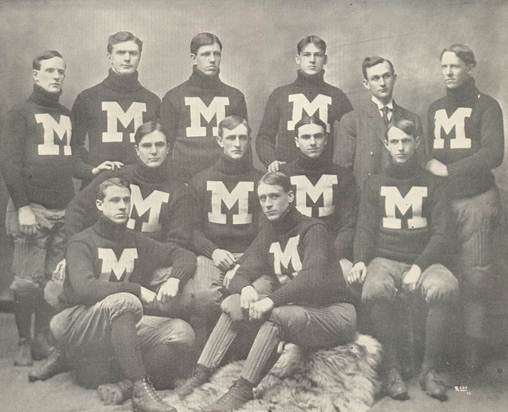

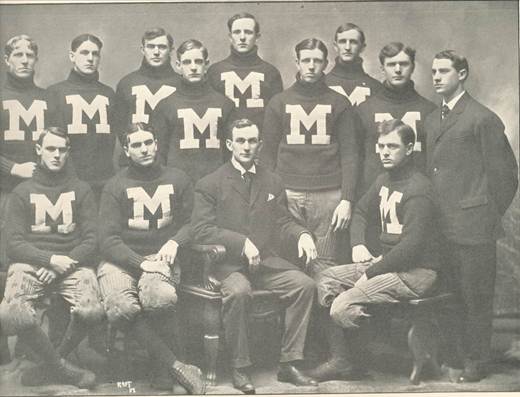

Team posing in front of Old Main

1905 team

1906 team

[1]

A History of

[2] Sarah Martha Williams was born in

[3] The

Chicago Tribune (Feb 23,

1902) noted that he was narrowly beaten in the forty yard dash by Archie

Hahn of

[4] There was a

[5]

The 1905-06 catalog listed

471 students (112 men, 111 women in the collegiate program; the rest in

the Music Conservatory); the 1906-07

catalog claimed 491 students.

No college was very large, in those days.

[6] This mid-sized house still stands

on the SE corner of the block, perhaps with an addition to the north

side made many decades ago. Olive (born 1878, teaching music in 1900)

was in the class of ’06 (she married John Burnside before graduating)

and Pansy, ’03 (born 1882) , remained at home to care for her father,

then her mother until becoming a music teacher at Bethany College in

Kansas, probably attracted there by her sister Olive living at Garden

City.

[7] The indoor track meets (before

[8] Produced by the junior class,

each Ravelings covered the

previous year. Thus, the 1907 issue covered 1905-06. That was a

particularly good issue, the editors having asked one person from each

graduating class to provide “a bit of history that will be of interest

and spicy.”

[9] The August Chautauqua brought

thousands to the campus for a week of lectures, music and picnics. In

addition to the Bryant Day, there were talks by Robert Lafollette and

Booker T. Washington. Later Billy Sunday came to town, and Andrew

Carnegie gave the money for a library.

[10] The first train to come down

from the north only derailed once! The track to

[11] Mark Benson, “T.R. and Football

Reform,” College Football

Historical Society (May 2003);

Bruce K. Stewart, “American Football,”

American History and Life

(November-December 1995), 24-30, 64, 66,

68-69. Theodore Roosevelt had already advocated this in

1893, “What I have to say with reference to all sports refers especially

to football. The brutality must be done away with and the danger

minimized…. The rulers for football ought probably to be altered.”

Harper’s Weekly (Dec. 23,

1893), 1236. On the other hand, he preferred sports that emphasized

“resolution, courage, endurance, and capacity to hold one’s own and to

stand up under punishment,” to calisthenics and gymnastics. As for

danger, horseback riding (his own passion), especially jumping, was more

likely to lead to death and injury. But above all, avoid encouraging

professional and semi-professional athletics; spectator sports, with

tens of thousands watching others, play is not healthy. Speech at

Harvard, June 28, 1905.

[12] Robin Lester,

Stagg’s University: the rise,

decline, and fall of big-time football at Chicago

(Urbana: University of Illinois, 1999); Morris Bealle,

The History of Football at

Harvard, 1874-1948 (Washington: Columbia, 1948), with a chapter

entitled “President Roosevelt Saves Football.”

[13] Thomas Brown (born 1845 in

[14] In 1903 the class rivalry

resulted in the junior class stealing the Civil War cannon obtained from

the federal government for display on campus. The conspirators dumped

the barrel into Cedar Creek where it remained for half a century, then

burned the gun carriage. Today the restored weapon is fired at the

Homecoming football game when Monmouth scores a touchdown.

[15]

Oracle (Nov. 1904).

[16]

Oracle (Nov. 1905). His

status as a faculty member was always in doubt. He was listed in 1906 as

“O. Clifford Bell, Athletic Director and Football coach.

[17] A.J. Taft (record

[18] Trap plays usually involved

double-teaming some defensive linemen, but allowing one to penetrate

into the backfield just long enough to be knocked for a loop by a

blocker coming full speed from one of the end positions. A swift back

would then dash through the momentary gap.

[19] Monmouth

Review (Sept. 6, 1905) gave a

detailed description of the games, Biggsville and

[20] In Amos Alonzo Stagg’s memoire,

Touchdown! (New York:

Longmans, 1927), 239-41, he only discussed the narrow loss to Army and

the new rule making it illegal for a kicker to recover the ball.

[21] The

Ravelings of 1907 has this correct in the narrative of the 1905

season, wrong in the listing of games; also the

[22] For the

[23]

Ravelings of 1907 contains one

picture showing Bell with his team lined up in the single wing in front

of Old Main, others show athletic competitions, including shots of the

bleachers, the onlookers, and the football team awaiting the snap.

[24] As usual, the

Review (Dec. 1) reported

play-by-play, noting that this was the “hardest and fiercest fought game

of the season,” with the score only 6-0 at half-time. One back jumping

clear over an onrushing tackler clearly thrilled both players and

spectators. Moreover, “Coach Bell threw a spectator over the fence for

gassing back when ordered off the field of play.”

[25]

Review (Sept 20, 1906): “Knox

students to play Socker.” Football was dropped for one year, until it

was discovered that “soft” football was as rough as “

[26] The

Oracle (Dec. 1905) reported

that “one of the great problems of the past has been to get the men to

take care of themselves, to observe the proper diet and to keep early

hours.” This reflected his intention “to make up for the lack of weight

with quick concerted action.” For the moment, however, pies and cakes

were in abundance.

[27]

If the suit seems a bit too large for modern tastes, the advertisements

in the Review (including some

for the Model, which closed

only in 1994) show that he wore exactly what was expected of a well-bred

gentleman.

[28] Two Princeton coaches, Herbert

Orin Crisler and Elton Ewart Wieman, summarized the changes in

Practical Football. A Manual for

Coaches, Players and Students of the Game (New York: McGraw-Hill,

1934), 6-7, as establishing a line of scrimmage, on which six men had to

take a motionless stance, pushing or pulling the ball carrier, defining

a legal forward pass, and doubling the distance for a first down. Among

the coaches’ advice: start the season with two or three weak opponents,

and, later on, use common sense.

[29] The obituary in the

Review (June 25, 26, 27,

1906) noted that his seven children were present for the funeral at the

United Presbyterian Church in Biggsville. Cliff and Harry of Monmouth

were among the pallbearers, and that Cliff was “summoned from Arcola,

where he has been for a few days.”

[30]

Review (Sept. 18, 1906):

“Varsity Men Desert the Game. Coach Bell Alarmed.”

[31]

Review headline of Sept. 27th:

“Big Football Pow Wow.” The 1908

Ravelings noted for that date “Football revival after chapel. Many

converts.”

[32] Although passes had been

attempted before,

referees usually whistled the play dead. The first legal forward pass

was thrown on September 4th at

[33]

Review (Oct. 15, 1906),

noting that the team “relied but little on the heavy mass football of

former years.”

[34]

Review (Oct 19, 1906).

[35]

Review (Oct 29, 1906). 550

yards offense versus 230, and Monmouth cleared $50-60.

[36]

Review (Nov. 1, 1906).

[37]

Review (

[38]

Review (Nov. 26, 1906). The

punting game was impossible: the ball “preferred to go no more than 15

or 20 yards on the kicks and kept the players guessing which direction

it was taking. Fake plays were tried but with little success, as the

slippery field and ball made it extremely difficult to handle.” The 1908

Ravelings reported: “Two

touchdowns by straight football gave Monmouth her victory.” In fact,

there had been so much rain that fall that passing was difficult, and

his swift runners had to pound their way through mud.

[39]

He coached the Monmouth football teams in 1911 and 1912; his men had

difficulty scoring, but still had a record of 6-10; the basketball

record was better—16-11. The 1935 and 1943 alumni directories located

him in the Hibbing (Minnesota) Public School system as Director of

Physical Therapy. He died April 21, 1950.

The Census of 1930

found him in Hibbing, age 47, teaching, married to Ethel, age 44, with

son Robert S, age 14. She was the Mary E. Senseman living in Alexis in

1910, a teacher in the local school and simultaneously listed as living

in Monmouth with her parents, but born in 1890. Most likely they met at

the 2nd Presbyterian church when she visited her family on

weekends. Mary Ethel McMillan died in Hibbing in 1945. The obituary in

the Hibbing Daily Tribune

listed survivors son Robert and brother Edward McMillan.

Robert Sensman McMillan

(April 4, 1916 - March 14, 2001 ) started his own architectural firm

Robert S. McMillan Associates, which concentrated mainly on projects in

Africa and the Middle East.

[40] In 1905 eighteen had died and

150 were seriously injured. The decrease was most marked among high

school players, where only one death was attributed to rough play. Blood

poisoning from broken blisters was more dangerous. Deaths from “partisan

rioting” were not counted. There was not a single fatality in the major

university games. Of injuries broken legs and collarbones were most

common, outnumbered only by severe sprains.

[41] The president of

[42] Since plays were called by the

captains, there was little for a coach to do except send in an

occasional substitute (and perhaps swear now and then).

[43] There were only four eligible

young women on the faculty, some widely traveled and all fully involved

in college life. Gertrude Henderson taught elocution, drama and

gymnastics. A member of the honorary Conglomerated Order of Mind

Enlighteners, she fielded the first women’s hockey team, probably using

the

[44] The

Review’s extensive coverage

of the November 9th parties (“Peanut Night Was Big Event”)

did not mention

[45] The

Review only referred to him

on those occasions when he acted as referee: January 10 and February 23.

The women began intercollegiate competition this winter, playing in the

Armory, but

[46] Reid’s record over the next

three seasons was

[47]

[48] Monmouth’s current coach, Steve

Bell, now in his tenth year, went 10-0 in the 2009 regular season. No

relation.

[49] Speech at the Harvard Union,

February 23, 1907. Speaking to the Cambridge Union May 26, 1910, he

added, “One of the things I wish we could learn from you is how to make

the game of football a rather less homicidal pastime. I do not wish to

speak as a mere sentimentalist…. I wish to deprive of any argument those

who I put in the mollycoddle class, of any argument against good sport.”

[50] Founded in 1908, it was the

first public trade school in the nation. It was, according to the alumni

website, a sports powerhouse.

[51] The obituaries (June 1 and 7,

1915) noted the presence of “O.C. Bell and Pansy Bell of Cleveland,

Ohio.”

[52] Like East Tech, West Tech

emphasized technical training. After acquiring its new building in 1922,

it became the largest high school in

[53]

A History of Cuyahoga County

and the City of Cleveland,

III, 20; and R. Y. McCray,

Representative Clevelanders: a biographical directory of leading men and

women in present day

[54] Pansy, by then forty-seven, was

in

[55] In the Census of 1900 she was 18

(born April 1882), her elder brother was a bookkeeper, her elder sister

in college; in1920 she fudged a bit, taking two years off her age; she

was a teacher living in