|

|

|

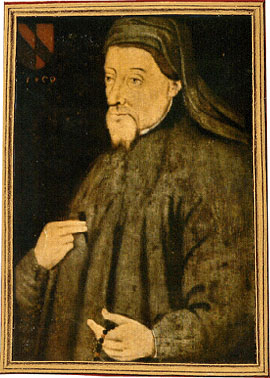

TextChaucer, Geoffrey. The Riverside Complete Works of Chaucer. Ed. Larry D. Benson. New York: Riverside Press, 1998. |

|

Some Initial ThoughtsMost of you come into this class with varying degrees of dread about it. Some of you worry that it's one of three times a week is too much for something this old. Just remember: caffeine is your friend (just as it will be mine, as well). Some of you worry that it's going to be about that sometimes-annoying person who popped up in A Knight's Tale. (No, Chaucer never had a gambling problem.) Most likely, though, you're going to be dreading this course, well, because it's CHAUCER and, you know, CHAUCER is a dead white guy who wrote funny. Dead language, dead references, dead to us. Dead wrong. In his original Middle English Chaucer may be alien but he's nowhere near dead. Sometimes he waxes philosophical, sure, or religious, or literary in ways you might find off-putting. However, once you get the basic vocabulary down -- "benedicte!" is always going to be "(the Lord) bless you!" as an interjection; "dynynytee" is always going to be "divinity" -- you're going to find that Chaucer is also clever, witty, a great poet and, sometimes, guffaw-inducingly funny. We'll work on ways to approach the Middle English language and history so that the fourteenth century seems a bit less removed than it does now. And what I hope you come to realize by the end of the semester is that Chaucer wrote some of the most vibrant language and art of his day.

|

|

The CourseNo real surprises here: we're going to read Chaucer's works -- short, middle, and long -- culminating in his Canterbury Tales. If you flip through the Benson, you're going to find that Chaucer wrote a heckuva lot more than the one work he's most famous for and we're going to sample those pieces here. However, it is the Tales which mark something new and startling in literature, the real roots of the tradition we call "Modern English Literature" (we'll talk about that "modern" later). However, the literature by itself isn't going to be sufficient to "get" Chaucer. There's simply too much time and distance between circa 1400 England and 2004 Illinois. What I'm going to ask of you, then, is that you help fill us in on all the gaps that need filling: this, of course, means oral presentations. There will also be two essays due in here, as well as two tests to think about.

|

|

|

The Reading Aloud ThingYou will be reading Chaucer aloud. Get used to the idea. You'll also be translating him aloud. Get used to the idea. Again, The Tales were oral stories first (and many of the poems were oral, as well) and I want you to get some sense of his ear as a poet and his craft as a writer -- and the best way to do that is to read him aloud. It also doesn't hurt your knowledge of the language (either Middle or Modern English), either.

|

GradesNot much to say here. Be in class and talk in class, because I'm going to base part of your evaluation on your participation. Right now that means that I'm giving you four skips during the course of the semester to be yours and yours alone; I don't care why you're not there. More than that, however, and it will count against your grade. I'm a great talker, but I do it best and most comfortably when there's a real conversation going on. So, you're going to be evaluated on how well you hold up your end of the conversation.

|

Percentages:

Essay One 15

|

Course Objectives

|

The Mellinger Learning CenterThe Mellinger Writing Center is available for all students: strong as well as inexperienced writers can benefit from suggestions and help from others. Even professional writers get feedback from colleagues, friends, and editors. Our writing fellows provide confidential help with any stage of the writing process: generating ideas; organizing paragraphs; writing introductions, conclusions, or transitions; or developing an analysis or topic.

Plagiarism Finally, a word about cheating. DON'T. This is really simple: if you copy someone else's direct words or exact ideas -- intentionally or not -- without giving them credit you fail the class. Universities and colleges are built upon the notion that ideas matter; if you plagiarize someone else's ideas, you're denying that fundamental tenet. Thus there will be zero tolerance for plagiarism in here. If you do it, you will fail the course, period. (Please see also p. 24 "Academic Dishonesty" in the college's 2004-05 catalog and Section 54 of Hacker's Bedford Handbook.)

|

Precision in Writing

Writing is central to the English major; therefore, the Department of English has implemented a policy to encourage excellence in writing:

The faculty in the Department

of English will return papers written by English majors, if they

Instructors will return papers, final papers will be reduced by one letter, and students will have forty-eight hours to revise and re-submit papers. In many cases, instructors will not have read the entire paper once they have determined that an essay fails to meet the minimum requirements; consequently, students will need to review and revise essays from beginning to end to make corrections. If essays fail to meet these minimum standards after re-submission, students will earn Fs for those assignments.

|

|

Date |

Class/Reading Abbreviations found on Benson 779 |

Presentation/Writing |

|

8/29 |

Syllabus -- Whoo Hoo! |

Chaucer's Life |

|

8/31 |

Benson's sections on "Pronunciation" xxx-xxxiv & "Versification" xlii -- xlv |

Chaucer's Language: A Crash-Course in Middle English |

|

9/3 |

"Complaint of Chaucer to His Purse" |

|

|

9/5 |

"Lak of Stedfastnesse" |

Politics |

|

9/7 |

"The Former Age" & "Fortune" |

|

|

9/10 |

PF |

|

|

9/12 |

PF |

Medieval Love |

|

9/14 |

PF |

|

|

9/17 |

The Canterbury Tales: GP |

|

|

9/19 |

GP |

Frame Narrative |

|

9/21 |

GP |

|

|

9/24 |

GP |

|

|

9/26 |

GP (esp. Friar, Franklin, Cook) |

Social Hierarchy |

|

9/28 |

GP (esp. Wif, Parson, Plowman, Miller, Reve) |

Come |

|

10/1 |

GP (esp. Summoner, Pardoner, Host, and end of GP) |

see |

|

10/3 |

loose ends of GP; start of KnT | me |

| 10/5 |

KnT |

about |

| 10/8 |

KnT |

rough drafts |

|

10/10 |

KnT |

Essay One Due |

|

10/12 |

KnT |

|

|

10/15 |

Fall Break |

|

|

10/17 |

KnT |

|

| 10/19 | MilT | |

|

10/22 |

Mid-Term Exam |

Better Check the STUDY GUIDE |

|

10/24 |

MilT/RvT |

|

|

10/26 |

RvT/CkT |

|

| 10/29 |

MLT |

|

|

10/31 |

WBP |

|

|

11/2 |

Class Cancelled |

|

|

11/5 |

WBP |

|

|

11/7 |

WBP/WBT |

Marriage & "The Marriage Group" |

|

11/9 |

WBT |

|

|

11/12 |

ClT |

|

|

11/14 |

ClT |

|

|

11/16 |

MerT |

Religion |

|

11/19 |

MerT |

|

|

11/21 & 11/23 |

Thanksgiving Break |

|

|

11/26 |

FranT |

|

|

11/28 |

FranT |

|

| 11/30 | Thop + Monk's Prologue | Essay Two Due |

|

12/3 |

FrT | |

|

12/5 |

SumT |

Chaucer's Literary Antecedents |

|

12/7 |

PrT |

|

|

12/10 |

NPT |

|

|

12/12 |

Retraction |

|

| 12/17 |

Final Exam 1:00 p.m. |

MilT